Hunter Sallis: Backdoor Cuts

More on some of the creative ways Wake Forest leverages the off-ball movement of its best player

After testing the 2024 NBA Draft waters, Hunter Sallis returns to Wake Forest as one of the top tough shotmakers in the country. Sallis created magic as a pull-up shooter while also scoring efficiently in the short midrange with his runner. According to Synergy Sports, Sallis ranked eighth nationally with an effective shooting rate of 52.6 percent on off-dribble jumpers — among players with 150+ field goal attempts.

As it has it years past, Wake Forest’s offense proved to be a positive environment for a talented transfer guard. Sallis saw his usage (14.3 percent across two seasons with Gonzaga, up to nearly 24 percent at Wake) and efficiency soar as his quickly established himself in Winston-Salem.

Here’s a look at pick-and-roll possessions used by Sallis (possessions ending with a FGA, shooting foul drawn or TOV committed) dating back to his time at Gonzaga, via Synergy Sports. The uptick was dramatic.

Gonzaga, 2021-22: 14 possessions, 3-8 FGA, 0.57 points per possession

Gonzaga, 2022-23: 29 possessions, 8-21 FGA, 0.76 PPP

Wake Forest, 2023-24: 132 possessions, 48-98 FGA, 0.98 PPP, 38.5 3P%, 52.8 2P%

Wake Forest utilized a short rotation last season; bench players accounted for only 20.4 percent of the team’s minutes, per KenPom, which ranked 351st nationally. The lineup of Kevin Miller, Cameron Hildreth, Hunter Sallis, Andrew Carr, and Efton Reid played 406 minutes together last season, according CBB Analytics. This was nearly 300 minutes more than Wake Forest’s next closest lineup, which featured Miller, Hildreth, Sallis, Carr and Zach Keller: 115 minutes, although 66 of those minutes occurred in the first seven games while Reid was forced to sit out, per Pivot Analysis.

Despite the paired down rotation, Wake Forest’s offense was rather egalitarian. This wasn’t a heliocentric scheme tailored to boost Sallis for his breakout season. All three of the team’s primary perimeter players posted usage rates above 21 percent and assist rates north of 12 percent. Boopie Miller led in both categories: 26.3 percent usage rate and 21.4 percent assist rate, per KenPom.

Wake Forest, of course, played through its frontcourt tandem of Carr and Reid, both of whom are skilled bigs who can pass and post-up mismatches.

So, while Sallis played on the ball plenty, as Wake launched lots of Big Guard/Wing pick-and-rolls from various Horns Out and Iverson sets, Sallis had to function as an off-ball mover, too. The Gonzaga transfer scaled perfectly to that role as well: 40.6 3P% off catch, 1.11 points per spot-up possession.

Capable of scoring out of the pick-and-roll or while coming off screening actions, Sallis possessed significant gravity within Wake Forest’s offense. Opponents had to scheme for his activity.

If he’s operating out of the pick-and-roll, then both defenders involved in the action must account for his pull-up jumper — the guard defender must navigate the screen and recover to contest from rearview pursuit while the big man defender may need to play closer to the level of the screen, which can up things up for the diver.

Here, Wake Forest runs Horns Out for Hildreth, which flows into empty-corner (or “Naked Corner”, as Steve Forbes would call it) pick-and-roll between Sallis and Reid. Georgia Tech puts two defenders on the ball, and with an empty side, there’s no help defender to tag Reid.

Sallis is a shifty off-ball player. He can manipulate chase defenders with upper body fakes and get to his spots with quality footwork. If his gravity forces defenses to put two on the ball or awkwardly veer-back switch on the fly, then it opens up other passing windows.

On this possession, Wake Forest runs “Chin Ricky” — guard-guard handoff action to initiate the possession, with another guard lifting up on the weak side (Abramo Canka), followed by a back screen for Sallis. Reid’s back screen for Sallis, however, is immediately followed by a re-screen (“Ricky”) pindown for Sallis. The curl is perfect as Sallis glides into the teeth of the defense, which forces Guillermo Diaz Graham to switch out while Jaland Lowe tries to veer back to Reid. He’s too little, though, and it’s too late. Sallis lobs to Reid for an easy slam.

As Sallis commands this type of respect and attention from ACC defenses, it allows him to open things up for his teammates as a screener, which I touched on over at Demon Deacon Digest back in February, or shake loose as a cutter within the half-court offense.

Forbes and his staff do an excellent job leveraging this gravity in situational basketball with backdoor cuts.

Wake Forest starts in a Horns set at Boston College. Hildreth enters the ball to Carr at the elbow and cuts through to the left. Carr initially looks left as the Hildreth gets set to run off the staggered screens (“Strong”) while Sallis walks up from the corner to the wing.

With only a one-point lead, Carr goes through his progressions — shifting back to the right side of the floor — and looks prepared to run a handoff for Sallis. Worried about sticking with Sallis on the handoff, Donald Hand jumps out and Sallis counters by darting backdoor for the dunk.

Here’s a late-game after-timeout (ATO) beauty from the win over Florida. Miller fakes and keeps a handoff for Hildreth, who clears to the weak side of the floor. With the entire defense lifted, Sallis sprints left-to-right across the baseline — as if he plans to receive a pass or handoff from Miller. Riley Kugel overcommits on Sallis, who uses the spacing to cut backdoor. Alex Condon does well to recover and contest at the rim, but Sallis finishes well through contact.

Let’s examine another impressive backdoor set vs. Pittsburgh. To start, here’s a bit of play sequencing from Wake Forest, which sets things up.

Wake Forest starts in another Horns set — two bigs at the elbows, two guards in the corners — and runs a variation of “Twist” action. Sallis starts in the left corner. Miller passes to Damari Monsanto, who quickly touches it back to Miller. As Miller looks to attack off the exchange, Carr lifts as if he’s going to set a ball screen for Miller. Instead, Carr “Veers” out — faking the screen for Miller — and sets a pindown for Sallis. Bub Carrington does a nice job sticking with Sallis, and the action flows into an angled ball screen from Carr. Sallis scores through contact in the paint.

Later in the game, with Carrington still on Sallis, Wake Forest starts the action the same way. Miller passes to Carr, who flips back to Miller. Reid lifts as if he plans to set a ball screen from Miller — only to veer out in the direction of Sallis. This time, though, Sallis takes off in the direction of Reid, which causes Carrington to react, and then cuts backdoor.

The lob from Miller has to cover a lot of ground and is maybe a touch late. As such, the Pitt defenders are able to get back and prevent a dunk by fouling Sallis. However, if the play is timed up perfectly, Sallis is dunking this thing.

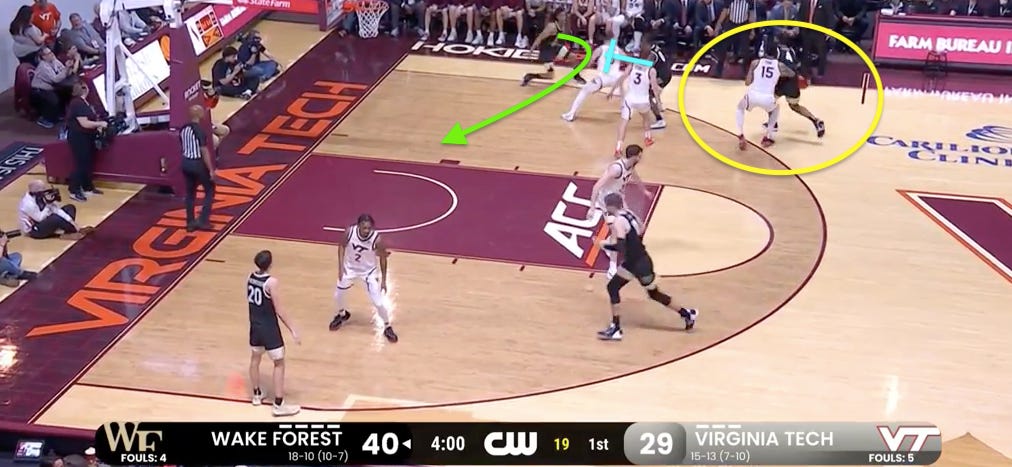

Up at Virginia Tech, Wake Forest morphs from what looks like Horns into a 5-out set with “Zoom” action (pindodown into handoff) for Sallis coming out of the right corner.

Miller is ready to set the pin for Sallis with Reid awaiting on the dribble-handoff. With Hunter Cattoor top side, Sallis counters by faking the Zoom action, planting his foot and v-cutting backdoor. Sallis is open behind the defense, but Reid’s pass is deflected out of bounds.

Here’s another ATO backdoor set for Sallis — this time at UNC. Wake Forest emerges from the timeout in its Diamond formation: Sallis under the rim, the two bigs stationed on opposite sides of the lane, and Parker Friedrichsen at the nail. The action will start with Sallis coming off a down screen from Monsanto, out to the right wing.

Sallis doesn’t receive a pass from Miller. Instead, Monsanto cuts up to the elbow, gets the entry pass from Miller, as Sallis tries to plant-and-cut backdoor on Seth Trimble. This is essentially “Blind Pig” action from Wake Forest, but Trimble, a strong defender, doesn’t take the bait. This is where Wake Forest can lean on the size and shotmaking of Sallis.

According to Bart Torvik, 81.8 percent of Sallis’s 2-point field goals last season were unassisted. He’s a bucket-getter.

One of Wake Forest’s go-to pick-and-roll actions starts in a Horns Out set — with the 2 or 3 popping out and the 5 lifting to set a ball screen near the slot. Hildreth and Reid work this pick-and-roll expertly vs. Pitt’s hedge coverage. Diaz Graham lunges out at Hildreth as Friedrichsen shakes up, taking Lowe — who should be ready to tag Reid — up the floor. Pitt has two defenders on the ball and there’s no one home to tag Reid. That’s a 7-feet, 240-pound freight train going downhill with nothing in his way.

Notice on this play, though, the inaction from Monsanto. He remains in the corner. Often, Wake Forest will have these two weak-side players exchange — the corner man floats up to the wing while the wing player drifts down to the corner.

That isn’t what happens here: Monsanto remains stationary in the corner. He even instructs Sallis to stay high. Regardless, both players stick on that side of the floor.

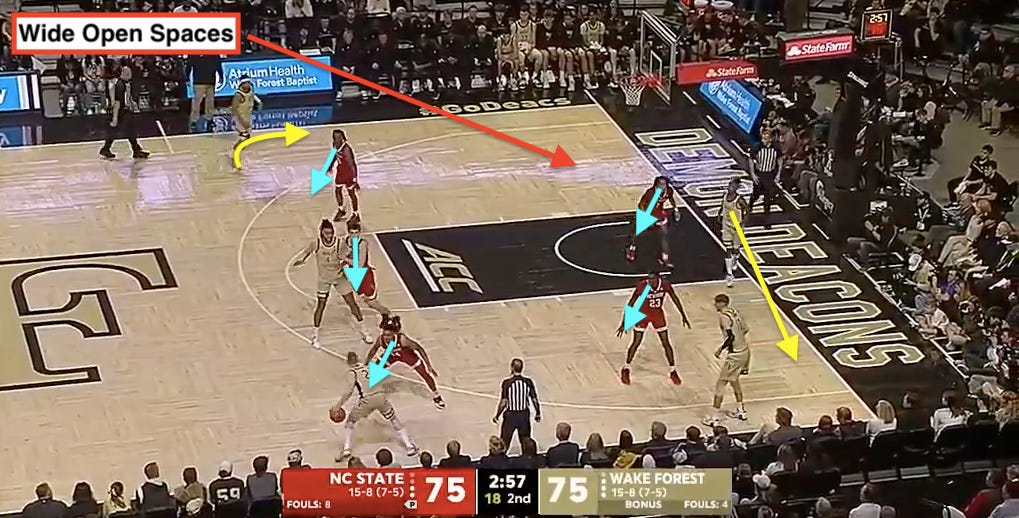

From the game in Winston-Salem vs. NC State: here’s a backdoor counter to this action. With the score tied at 75, Forbes and his staff draw up a gem. As Hildreth pops out and takes the pass from Sallis, Reid lifts as if he wants to set a ball screen. NC State’s defense is ready for the screen-roll — loading up, with five sets of eyes dialed in.

While this happens, though, Miller doesn’t remain on the weak side; he cuts left-to-right and lands in the strong-side corner, next to Carr. The defense is tilted and lifted with Wake Forest overloading to the strong side, which leaves a lot of room for Sallis to play with — as DJ Horne gets caught looking in the cookie jar.

Another variation of Wake Forest’s pick-and-roll game comes from what I refer to as its “Horns Out Step” action. Generally, this produces spread screen-roll in the middle of the floor; however, there’s a backdoor counter to play off the ball screen action.

On this ATO set (“Horns Out Step Backdoor”), Hildreth pops out and Keller steps up to set a flat ball screen for Miller. The crossover from Miller catches Quinten Post on the wrong side of the screen, which allows Miller to easily turn the corner. Claudell Harris is gapped up and he momentarily loses sight of Sallis, located in the right corner.

As Harris turns back to the corner, it’s too late: Sallis is gone and Miller hits him with a perfect pocket pass.