The Maine Thing: Duke starts to work in small-ball around Cooper Flagg

Duke explores new lineup combinations and half-court actions around Cooper Flagg

When Jon Scheyer and his staff put the finishing touches on Duke’s roster for the 2024-25 season, it was undeniable that there was an exceptional amount of talent. With so many complimentary pieces, it was intriguing to consider potential lineup combinations and scheme options for a new-look roster, including how and when Duke would try to play a small-ball lineup around Cooper Flagg.

The Blue Devils obviously had the pieces to get to these lineups: a collection of like-sized guards and wings who can dribble, pass, shoot and defend. However, with the team’s logjam at the center position, it’s harder to justify downsizing. With Khaman Maluach, Maliq Brown and Patrick Ngongba, Duke has the most talented group of centers in the county, and yet there are only 40 minutes per game to divvy up for that trio.

The Blue Devils have dabbled with playing Brown as a 4 this season, though some of those minutes have come at the end of blowout win. According to CBB Analytics, Brown has played five minutes with Maluach (-2) and 10 minutes with Ngongba (+3). For the most part, though, those three platoon at the position with Maluach (19.9 minutes per game) getting the bulk of the minutes: Duke is +222 in 358 minutes with Maluach on the floor, including an offensive rating of 130.0 points per 100 possessions (99th percentile) and a defensive rating of 91 points per 100 possessions (99th percentile).

Basically, it’s hard to justify not having one of those guys on the floor; each center provides a different, valuable dimension. Maluach offers rim protection and vertical spacing for the offense with his ability to screen, roll and catch lobs. Brown has the fastest hands in the country, which he utilizes to cause havoc as a switchable defensive 5, while also providing passing from the high post. Maluach and Brown, especially, can both switch out on opposing guards, which also reduced the defensive need to go small in order to switch 1-5. Duke could play lineups that offered size and flexibility, which is what every coach desires. Ngongba is a little less defined, though his skills as a low-block scorer, handoff hub at the elbow and short-roll playmaker are right there, for anyone to see.

The injury to Brown — a right knee sprain suffered against Notre Dame — is a bummer. He’s an excellent player in the midst of another strong season. Moreover, Duke needs Brown’s two-way game to hit its ceiling.

That said, not only does Brown’s absence create up more opportunities for Ngongba, but it also opens the door for more lineups that feature Flagg as the nominal 5, surrounded by four guards, or at the 4 next to Mason Gillis as the de facto small-ball stretch-5. In theory, these lineups should allow Duke to grease the wheels on offense by putting five guys who can launch quick-trigger 3s, handle the ball in space and pass on the floor at the same time.

Duke’s hand was forced due to Brown’s injury; however, as Duke juggles two different timelines simultaneously — working game-by-game through an ACC slate, while also building things out for the postseason — now is the moment to tinker with lineups, work in new combinations and see what else lies hidden in plain sight among such a talented collection of players and personalities. This is the time for Duke to work in more small-ball looks around Flagg.

Early Indicators

During an exhibition game against Arizona State, Duke experimented some with Flagg and Gillis as a small-ball frontcourt 4/5 duo. Flagg, in a limited stretch, mostly worked as a screener for Caleb Foster in the pick-and-roll. Here, Foster attacks Jayden Quaintance in drop coverage, which collapses ASU’s defense and creates the ball reversal for an open Darren Harris 3-point attempt. Gillis grabs the offensive rebound and fires it back out for a catch-and-shoot Foster triple.

Whether it was simply the demands of the roster, or Scheyer wanting to keep these small-ball lineup combos as an ace up his sleeve — something to bust out later in the season in leverage minutes against an unsuspecting opponent — Duke played only two minutes with Flagg on the floor and Maluach, Brown and Ngongba on the bench through the first 15 games of the season.

Once more, this is where Brown’s injury shifts the calculus for Duke’s staff; while Duke could still split the 40 minutes of center each game between Maluach and Ngongba, barring foul trouble, the Blue Devils now have more situational opportunities to go small and juice the on-court product with added speed and shooting.

Plus, when Duke goes small — with Flagg as the tallest guy on the floor — it doesn’t have to completely sacrifice its rebounding edge or rim protection. Both Sion James (2.2% block rate) and Flagg (4.2% block rate) are capable of altering shots at the rim, especially when contesting from the weak side.

Bad (injury) luck against the Irish

To start the game at Duke, Notre Dame coach Micah Shrewsberry opted to cross-match at the 4 and 5 positions defensively. Notre Dame’s center, Kebba Njie (6-10, 250), was assigned to Flagg, while power forward Tae Davis (6-9, 215) took Maluach.

The logic behind the decision was, seemingly, to keep Njie, who is used primarily to hedge ball screens in Notre Dame’s defensive system, out of various pick-and-roll coverages. It was a strategy to avoid getting caught in rotation against an elite offense: when Duke ran its ball screen sets with Maluach as the screener, Notre Dame could switch Davis onto Duke’s guards, while one of their guards took on Maluach.

The Irish, under this approach, were willing to sacrifice something on the interior of their defense — placing a smaller guard on the 7-foot-2 Maluach — though given how infrequently Duke posts up Maluach, it’s a tradeoff they were willing to live with. If Duke wanted to break out of its offensive flow to throw the ball into Maluach in the post, that’d be a win for Notre Dame.

More generally, though, even a good defense can’t take everything away from a great offense; it must be selective and intentional with what it tries to take off the table. Notre Dame is well coached, but this isn’t a very good defensive unit: No. 155 nationally in adjusted defensive efficiency), per KenPom. If the Irish could manage keep the ball in front while defending screen-roll actions with Maluach, they could limit some of the downhill rim runs that drive Duke’s half-court offense. In the previous game at NC State, Notre Dame’s hedge coverages were burnt to a crisp by the Wolfpack; Ben Middlebrooks slipped screens and continuously put pressure on the rim, including what turned out to be the game-winning possession.

Well, on the very first possession of the game at Cameron Indoor, Duke took Notre Dame’s plan and threw it over the top rope. The Blue Devils ran Kon Knueppel to the middle of the floor off of a down screen from Maluach. Flagg, with Njie (14) on him, quickly lifted to set a ball screen for Knueppel — a setup Duke has used plenty this season. As Knueppel dribbled off the screen, Njie hedged out, which left Flagg open on the short roll. Flagg is excellent in these pockets of space, catching the ball around the free throw line and making plays with a 4-on-3 advantage. Flagg receive the pass from Knueppel around the nail and two Notre Dame defenders collapse on him — creating an easy lob opportunity to Maluach.

Less than two minutes later, it’s the same setup: Knueppel comes to the middle of the floor, Flagg lifts to set a run-out ball screen for Knueppel and Maluach sets an “Exit” screen along the baseline for Proctor — who cuts to the right corner. Once again, Njie hedges Flagg’s screen for Knueppel, which puts two defenders on the ball. Instead of short rolling, Flagg pops out above the arc this time. With Flagg wide open in the middle of the floor, Davis (7) must react. He leaves the paint to attend to the open Blue Devil atop the key. At the same time, Markus Burton (3) gets stuck on Maluach’s screen at the right block. The presence of Burton, between Maluach and the rim, takes away another lob opportunity to Duke’s center, but it also leaves Proctor (41.2 3P%) wide open on the wing.

Flagg is a quick processor and a quality decision-maker. According to CBB Analytics, Flagg has 15 assists to both Maluach and Proctor this season. In total, Flagg has 10+ assists to four different teammates: Maluach, Proctor, Knueppel (13) and Isaiah Evans (10).

Even when Maluach was used as a screener against Notre Dame, causing Davis to switch out on Duke’s guards, the Blue Devils still cooked.

On this possession, Maluach sets another run-out ball screen for James. Davis switches out. Braeden Shrewberry (11) now has Maluach and he fronts/face-guards the post. James dribbles right and pulls Davis further out from the rim, which helps open a crease in the middle of the floor for Proctor. James pitches back to Proctor, who catches the ball on the move and immediately attacks downhill — blowing by Burton, pulling Njie into the paint and creating the open kick-out 3-ball for Flagg in the left corner.

Ultimately, Notre Dame elected to adjust. The Irish pulled Njie off the floor and went to a full-time small-ball look — with Davis as the de facto 5. Njie played only 15 minutes at Cameron Indoor, his fewest in any single game this season.

Davis is a good driver and Notre Dame flipped to more 5-out packages on offense to take advantage of his speed and handle. For the most part, Duke didn’t blink and stuck with its base lineups and coverages. In fact, Maluach played a season-high 32 minutes, though in the second half of the game the big fella from South Sudan was again asked to switch out 1-5, which makes for a tricky cover against Notre Dame’s furious, nonstop conveyor belt of guard-guard screening actions. The defense must be prepared to rotate on a string and make multiple switches on every possession to properly contain this attack.

Elsewhere in the center rotation: Ngongba played five minutes against Notre Dame, while Brown was reduced to just 52 seconds of action before exiting in the first half with his injury.

This left two minutes to spare for lineups that featured Flagg without a traditional center on the floor — flanked by a combination of James, Proctor, Knueppel, Foster and Gillis.

Defensively, the Blue Devils switched just about every screen, regardless of position. Flagg starts this possession on Davis, but he quickly switches to Sir Mohammed (4) when Mohammed sets an early pindown screen for Davis in Notre Dame’s “Wide” action, placing James on Davis. As Davis drives late in the shot clock, now with Proctor guarding him in the right corner, Flagg returns as a help defender to contest/alter a shot at the rim.

It’s a small sample, but the center-less lineups with Flagg this season have held opponents to just 7-of-22 shooting from the floor (31.8 FG%, 34.1 eFG%), including 6-of-15 on 2-point attempts (40 2P%).

On the other side of the ball, Notre Dame mostly played zone against the small-ball crew. However, when Notre Dame matched up man-to-man, Duke instantly snapped into inverted pick-and-roll (a guard screening for a forward or center) with Flagg as the ball handler/primary initiator.

Here, Proctor gets bumped by Burton, his defender and the smallest guy on the floor, as he lifts to screen for Flagg. Duke wants Burton to be the screen defender with Flagg operating on the ball. This would force Burton to switch onto the taller Flagg or try to hedge-and-recover, which is especially tricky when the dangerous Proctor pops out in the opposite direction. To counter, Notre Dame pre-switches the action; Burton pushes Mohammed, who was on Foster to start, in the direction of Proctor. In theory, this should allow Notre Dame to more comfortably switch a Flagg-Proctor ball screen. Instead, Proctor ghosts his screen and slips out to the right while Flagg leverages that bit of misdirection to attack Davis 1-on-1 in the middle of the floor.

The freshman from Maine takes his time, gets to his spot and draws a foul. Rinse and repeat. Flagg has drawn 45 shooting fouls this season (3.2 per 40 minutes), which is tops on Duke’s roster by a lot, per CBB Analytics. Maluach is second with 18 shooting fouls drawn.

Notice, too, that James doesn’t space out above the arc — like Foster, Knueppel and Proctor — which would provide Flagg with four potential kick-out options. Instead, he drifts down to the dunker spot on the left side of the floor. When Duke goes 5-out around Flagg, James is often stationed in this area.

This spacing tactic provides Flagg with a potential interior passing option. If Matt Allocco (41) leaves James to double Flagg in the paint, Flagg has an easy pass to a rugged interior finisher who is located right in front of the rim. Plus, the 6-foot-4 Allocco, who has three total blocks this season, offers very little weak-side rim protection when Flagg drives deep into the paint.

Invert the action

Through the first half of the season, Duke ran plenty of inverted pick-and-rolls with Flagg as the ball handler and one of the guards — James, Knueppel, Proctor and Foster — as a screener. It’s a great way to generate mismatches for Flagg to attack, which has been an asset for the Blue Devils in some of their biggest victories of the season.

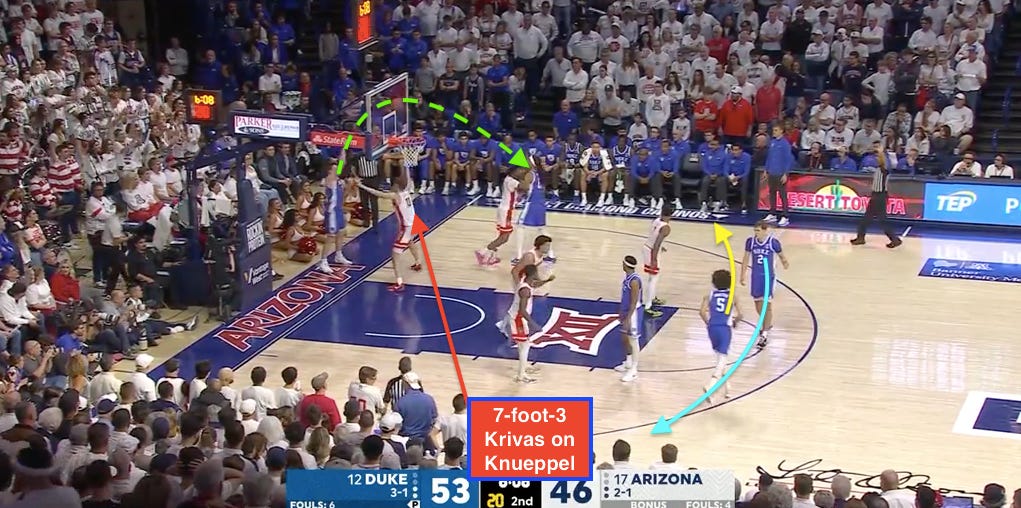

As I wrote about after the win in Tucson, Duke took advantage of how Arizona defended baseline-out-of-bounds (BLOB) plays — placing its center on the inbound passer, which in this case was Knueppel. This meant, once the ball was in play, the Wildcats had their largest and slowest player defending Knueppel, an excellent off-ball mover, shooter and passer.

Duke countered by clearing out one side of the floor for Flagg and then running inverted actions between he and Knueppel. This would force Arizona’s center to navigate the screen; switch to Flagg and be at a speed/skill disadvantage or try to hedge-and-recover while Knueppel slips out in the opposite direction.

On this possession, both defenders go to Flagg. Knueppel is open, but Flagg is able to glide around 7-footer Motiejus Krivas (14) and draw a foul.

Here’s the same setup from earlier in the second half. This time, though, Flagg pitches to Knueppel as he slips the inverted screen on the left side, moving toward the middle of the floor. Tobe Awaka (30) closes out, but Knueppel is able to shot fake and attack the more plodding defender on the drive. This pulls Carter Bryant (9) into the paint and creates a kick-out to Flagg.

Depending on the matchup, and when Duke wants to create a switch for Flagg to attack, the offense can have him set a ball screen for one of the guards. Often, this allows Flagg to go into the post against a smaller defender. Advantage, Flagg and Duke — even against a talented wing like Kentucky’s Jaxson Robinson.

Duke has worked these screening actions with Flagg and either James and Knueppel efficiently in both directions this season. By flipping the roles and having Flagg handle the ball screen while a smaller teammate sets the pick, Duke can still create the same favorable switches for Flagg. This approach allows him to attack with a live dribble and build momentum toward the basket.

When Duke knocked off Auburn in Durham, they played matchup ball down the stretch with Flagg. The Tigers like to switch a lot of actions. So, with the 6-foot-1, 175-pound Tahaad Pettiford (0) on Knueppel, Duke has Knueppel set the ball screen for Flagg. Pettiford switches and now Flagg has the matchup he wants. Flagg drives right against Pettiford, spins back left and finishes through contact for the crafty and-one bucket.

Similarly in the Notre Dame game: James has the 6-foot, 190-pound Burton on him. Scheyer instructs James to bring Burton to the middle of the floor for a dance with Flagg. James screens Davis, Burton switches to Flagg and it’s easy money for Duke.

On all of these plays, Duke has a 5 on the floor — either Maluach or Brown. When Duke plays Flagg with four guards or with three guards and Gillis, though, it can toggle the matchups and further amplify its spacing.

Keep the Maine Thing the Main Thing

Flagg has played 300 minutes (+184) with Maluach this season (53.6 percent of his total minutes), 213 minutes (+72) with Brown (38.0 percent) and 39 minutes with Ngongba (+39). Within these minutes, there’s some slight overlap, too: Flagg has played four minutes with Ngongba and Brown at the same time and two minutes with Maluach and Brown.

This is why the win over Boston College — as Flagg celebrated his homecoming back to New England with 28 points, five rebounds, four assists, two steals and two blocks — is so intriguing: it was the most minutes he’s played this season without a true 5 on the floor next to him. The Blue Devils are trying new things.

According to CBB Analytics, Flagg has played only 14 minutes this season without a center — nine of which came against Boston College. During that limited sample of game play, Duke outscored Boston College by nine points, while posting an offensive efficiency of 1.49 points per possession.

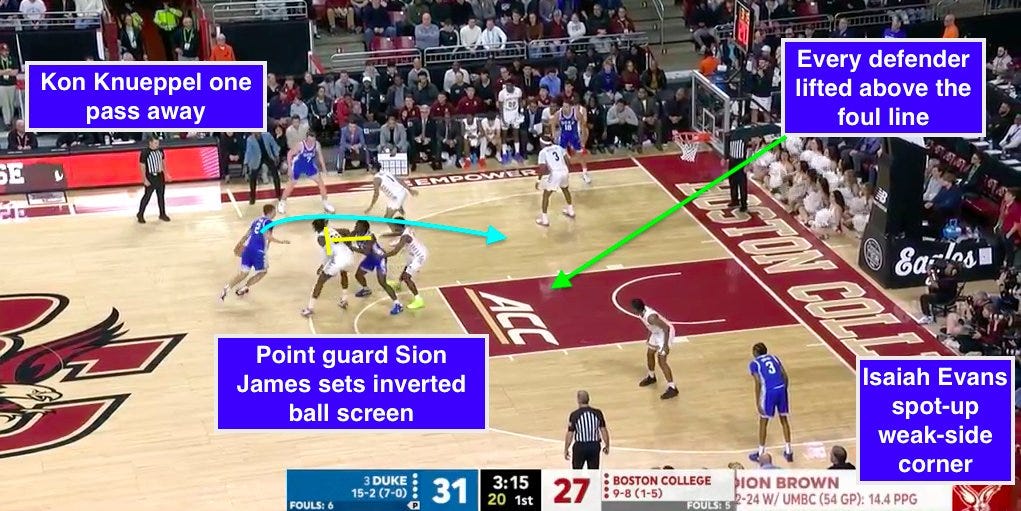

When Duke went small, BC countered with a smaller lineup of its own: four guards and backup freshman center Jayden Hastings (22). The Eagles also opted to have Hastings, the 5, match with Flagg while guard Dion Brown (1) checked Gillis. Unsurprisingly, Duke found this matchup to be favorable and went to more inverted pick-and-roll — with James screening for Flagg.

Inverted Pick-and-Roll

Here, Boston College tries to navigate the inverted ball screen with its backup center, Hastings, and point guard Josh Beadle. James screens and pops out, which places all four off-ball players above the arc. Boston College’s defense is compromised. This is a green light for Flagg: attack the rack.

Before the switch, Beadle sets up just below the level of the screen, which gives Flagg a runway to gather some steam as he drives left and spins back right for the and-one finish at the rim.

It should be noted that this type of successful matchup-hunting is the ministry of wing superstars in the NBA. If you buy into Flagg’s potential as one of the Top 5-10 players in the league at some point (*raises hand*), it’s in part because of what he offers as a big wing creator, one that can exploit different matchups and slash downhill against a variety of different-sized defenders.

After a timeout, on the final play of the first half, Scheyer schemes up more inverted pick-and-roll with Flagg. I refer to this set as Duke’s “2 Chase” action — with Proctor (defended by BC center Chad Venning) running up to set the first screen before ghosting out to the left wing, while James chases behind and sets the second screen for Flagg. Beadle switches out to Flagg, but Boston College’s defense, again including the 270-pound Venning (32) trying to hang in space, struggles with how to handle James diving to the rim. Every defender collapses on James, and Proctor is wide open for a great look for deep. Proctor misses, but this is an easy read for Flagg and a shot that Duke’s staff is very happy to generate.

Quick Pick-and-Roll

Of course, a more traditional pick-and-roll alignment can work, too. Following a miss, James and Flagg push the ball up the floor with pace and flow into a ball-screen action: Flagg, defended by Venning, screens for James. Venning hedges in the direction of James, which opens a pocket of space for Flagg on the pick-and-pop. Flagg is shooting a good ball in league play (14-of-28 3PA); when James passes back to Flagg, Venning is forced to hard closeout, which creates a catch-and-go drive opportunity. Flagg gets right to the rim and draws another shooting foul.

With Flagg setting this pitch-and-chase ball screen in early offense (look how close he is to James when he starts to run over and set the ball screen), it gives the defense very little time to call out and react to the action.

When Gillis (39.9 3P% career) plays next to Flagg in these small-ball groups, he can work as a potent pick-and-pop screener as well. This is one of the few half-court possessions that Flagg wasn’t directly involved in during the stints with Maluach and Ngongba on the bench. Gillis screens for Proctor, and Boston College switches the action. Proctor, with Venning now on him, takes him time to create some rhythm and launch a pull-up 3.

Pistol

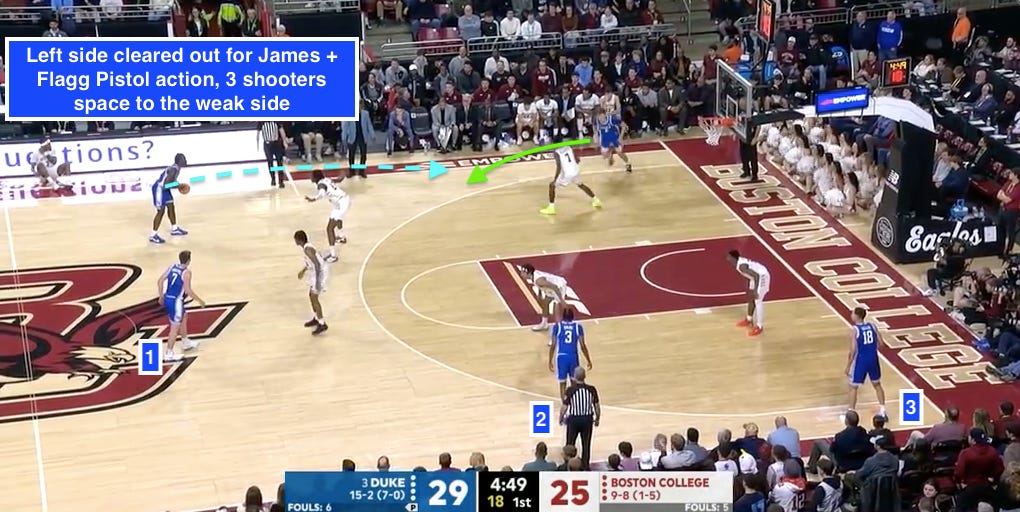

A new wrinkle that Duke introduced to its offense for these 5-out/small-ball lineups involved “Pistol” action between James and Flagg. Generally, Pistol is an exchange that takes place in early offense between two of the guards on either the right or left side of the floor — with one guard screening for the other or the two engaging in quick handoff actions, which can flow into a variety of secondary progressions.

Flagg is a roaming mismatch piece for Duke’s offense, thus he’s perfect to work in quick-hitting actions like this, both as a screener or a ball handler. When the offense plays with pace, these actions can scramble defensive assignments and screen responsibilities.

With about five minutes to go in the first half, the Blue Devils empty out the left side of the floor for James and Flagg, while three shooters space to the weak side: Knueppel in the right slot, Evans on the wing and Gillis tucked deep into the right corner.

That spacing template from Duke adds even more zest to the possession: if either James or Flagg drive to the rim, one of the weak-side defenders must help in the paint and that creates a potential kick-out opportunity.

The action starts with Flagg lifting to the left wing to receive a pass. As soon as James passes ahead to Flagg, he chases after the ball. That initial pass is followed by another quick pass — with Flagg flipping the ball back to James. The Pistol exchange between James and Flagg creates an on-the-fly screen-roll action for Duke. Boston College is also cross matched defensively here: 6-foot-1 guard Fred Payne (5) is on Gillis, but he’s also the low-man, back-line help defender. This means Payne is the player tasked with helping at the rim if there’s a drive.

Let’s see it in action. BC’s defense is caught on its heels as Beadle quickly tries to switch; however, he offers little resistance against the explosive downhill drive game of James. The Tulane transfer uses his burst to turn the corner and get to the rim — where nearly 46 percent of his field goal attempt this season have come from, per CBB Analytics.

James misses the rim attempt. The shorter Payne does just enough at the hoop to bother James. Regardless, it’s still a demonstration of good process for Duke’s offense: the Blue Devils created a high-percentage shot at the hoop for one of their best players, working off the gravity of Flagg.

During the second half, Scheyer called for this play again, although on this time Flagg opted to keep the ball. Flagg fakes a handoff back to James and drives into the the teeth of the defense, which pulls in a help defender. From there, Flagg kicks to Knueppel atop the key and flows into another quick ball screen action. Boston College switches the screen, but the defense bends as Chas Kelly (00) digs off the left corner and into the paint to help Donald Hand Jr. (13) as Flagg posts him up on a switch. James is open in the corner and there’s a seam to attack when Knueppel kicks the ball in his direction. Kelley closes out, but James is a bullet getting downhill and into the paint for a layup.

The fake handoff actions with Flagg are powerful and a good counter to a defense that wants to switch.

Given the proclivity of Duke’s staff for sequencing plays and creating new reads out of established offensive concepts, it’s a safe bet to assume that the Pistol action — with all of its different permutations — will remain a part of the playbook going forward. There’s just too much low-hanging fruit to grab here. (Evans, with his game-breaking shooting stroke, looms as a dangerous partner to work off of Flagg.)

Flood The Zone

In an effort to disrupt Duke’s half-court rhythm, Boston College tried a few (unsuccessful) possessions of zone defense — one of which occurred against the small-ball lineup. The Blue Devils didn’t blink. Duke spaces the court and, as the ball reverses sides of the floor, Flagg works as a cutter and flashes to the lane. James picks him out with a perfect pass and Flagg does the rest.

According to my charting, this marked the third time this season that James has assisted a cut dunk for Flagg. Overall, James has 23 assists on rim finishes this season, good for second on Duke’s roster — behind only Flagg (25).

James also has a 3.4-to-1 assist-to-turnover ratio in conference play. He’s been excellent this season.

Gut Stagger: “L”

Duke has tapped into the off-ball movement of Knueppel frequently this season; it’s one of the core competencies of this offense. Knueppel’s gravity as a shooter loosens up opposing defenses and creates pockets of space for his teammates.

The most popular of these concepts, which I refer to as “Gut Stagger” or “L”, starts with Knueppel in the left corner. Knueppel will launch things by running up the middle — the gut, if you will — of the lane off of staggered screens from Flagg and the center, typically Maluach or Brown. Knueppel’s movement pattern looks like the letter L.

Often, this play has been used to launch middle pick-and-roll with Knueppel and Maluach. However, Duke also likes to use this design to create a post-up for Flagg. In this arraignment, Flagg will screen for Knueppel and then quickly seal in the post. Following the seal, the left side of the floor is cleared out and James has a good angle to toss in a post-entry pass.

This, however, is the first time Duke’s run this action this season with it’s small-ball lineup on the floor. Knueppel takes the L Train up the middle of the lane with Flagg and Gillis as the screeners. Flagg screens and seals. BC still has Hastings (6-9, 240) on Flagg, so it’s not like there’s some overwhelming size mismatch for Flagg. That said, he faces up and drives right through Hastings for another bucket in the paint.

And while Duke has scored off this action with Flagg several times this season, it’s worth nothing what the Blue Devils do with their spacing here — because it’s more than just putting four shooters around Flagg.

After James throws the entry pass to Flagg, he cuts back down the dunker spot. Meanwhile, Knueppel is one pass away; if BC wants to dig down or double team off of the strong-side wing, Flagg has an easy kick-out pass to Knueppel (37.6 3P%). If a second defender comes from the weak side, Flagg will be able to hit James for a layup at the rim, or he’ll have plenty of time to kick-out for a spot-up 3 to Gillis or Evans.

By placing James, Duke’s point guard, in the dunker spot, Scheyer is again borrowing from the Boston Celtics, who like to deploy guards Jrue Holiday and Derrick White in the dunker spot — while working off the dynamic creation efforts of big wing playmakers Jayson Tatum and Jaylen Brown.

This maneuver pulls size and weak-side rim protection for the defense away from the paint, leaving the smallest defender on the floor as the best option to help contest Flagg at the rim. This isn’t random. That’s intentional.

James, like Holiday and White, is a strong interior finisher, too. If his defender tries to double Flagg, then it’s a quick drop-off pass to James for a layup.

For comparison, here’s how compressed the defense can play when Duke goes to Flagg in the post — with a true 5 on the floor and James spaced one pass away on the strong side wing, as opposed to the dunker spot.

Going back to the first game of the season, this is the same read from the same set. However, there’s more size and congestion in the lane, along with fewer weak-side kick-out options. Flagg, of course, still manages to draw a foul while fading away from the rim — instead of powering toward it.

Flagg has a nearly unblockable jumper that he can wield whenever he wants; according to CBB Analytics, Flagg has made 57.8 percent of his 2-point attempts that are in the paint but away from the rim (outside of 4.5 feet). He’s obviously a magnet for contact, too. Put those traits together and he can still do serious damage in the post with Maluach, Brown and Ngongba on the floor. That said, the approach is different.

Later in the second half, Duke runs the same play. Proctor runs the L this time with Knueppel on the bench. Flagg seals in the left mid-post. This time, though, Boston College elects to double and sends a second defender at Flagg. As James cuts from the left wing to the dunker spot, his defender, Payne, doubles Flagg. Venning must come off of Gillis, who pops from the foul line area to outside the arc, to prevent an easy give-and-go pass from Flagg back to James for a layup.

With Gillis popping out, Luka Toews (10), who was assigned to Proctor at the outset of the possession, must come off of the weak-side wing to help prevent a kick-out to a shooter one pass away. Now that BC’s defense is in rotation, Flagg shifts to Playmaker Mode. He uses a reverse dribble to create some separation from the post double and open up the court. Freeze the play, there are four BC defenders on one side of the floor to guard three guys. This leaves only one defender, Hand, on the weak side against two lights-out shooters: Proctor and Evans (45.7 3P%).

Flagg scans the floor and makes a great read — he skips the ball to Proctor on the opposite wing. The passes happens quickly; Hand isn’t able to break on the ball, and he’s reduced to closing out on Proctor, with Toews on Gillis. That’s all fine and dandy, but that closeout leaves Slim Evans — the last guy in the building you want hitting off of a tee if you’re a Boston College partisan — wide open in the corner. It’s going up.

As always, Proctor, a talented connector, makes the extra pass, swinging to the corner for an Evans triple and a hockey assist for Flagg.

Defense: Keep the ball in front

The primary setup for Duke’s half-court defense with these lineups on the floor will feature a lot of 1-5 switching. This was the base pick-and-roll/DHO coverages at Boston College, though there were a few possessions of Gillis and Flagg in drop coverage, per my charting.

Gillis is sturdy enough to bang with opposing centers in the paint and he has the lateral capabilities to switch out and hang with guards in space along the perimeter. When Duke talks and switches around, the Blue Devils can keep the ball in front, create turnovers and force opponents to attempt tough, off-dribble jumpers late in the shot clock.

Here, the Eagles try to run their continuity ball screen offense. On the left side of the floor, Dion Brown (1) runs empty-corner pick-and-roll with Hastings. Duke switches the screen: Gillis takes Brown and Flagg lands on Hastings. Brown throws a poor entry pass to Hastings, who doesn’t really have all that good post position. Flagg uses his length and fast hands to swat away the pass and force a turnover.

Boston College ran this “Horns Twist” action dozens of times against Duke. As Kelley dribbles left off of the first screen, Flagg sinks below the level of the pick in drop coverage. Vennings lifts and creates the Twist action with a second ball screen that brings Kelley make to the middle of the floor. Gillis switches the second screen and easily bottles up a drive from Kelley, who bumps into the bulky defender and gets pushed back out to the corner. Next, the ball is swung around the arc as precious seconds drain from the shot block. This also provides Duke with a window to switch behind the play; Gillis switches back to Venning and Proctor takes Kelley on the wing. Finally, with 10 seconds left on the shot block, Vennings sets a high ball screen for Payne. Once more, Duke switches the action: Gillis on Payne and Evans takes Venning.

This is where Slim’s growth as defender shows up. As Roger McFarlane (3) launches a late-clock 3-point attempt, Evans handles his assignment and — despite giving up nearly 100 pounds to Venning — boxes out Boston College’s center. When Duke’s young wings are willing and able to handle these types of tactics, it makes them more playable and these small lineups more viable against ACC foes.

The links don’t work for the videos in the article.