Hedge Your Bets: Wake Forest wins with scheme adjustment

With a few notable tweaks, this season's Wake Forest team is led by its aggressive approach on defense

Editor’s note: For whatever reason, I’m having problems with the the video embeds in this story — along with all of my previous posts. Not great, folks! The video files meet Substack’s format and size requirements, and I’m able to upload them on the back end, but they’re unresponsive for me across multiple browsers, both desktop and mobile. I’ve heard from several readers who are experiencing these issues, too. I’ve tried troubleshooting, but so far, no dice. The videos are, however, working through the Subtstack app. This is a bummer; it’s not how I planned the release of this story, obviously. However, I want to get it out before the weekend. Apologies for the inconvenience. Again, you should be able to read and watch the videos through the app if you so chose. Hopefully this can be sorted out soon. In the meantime, I’ll continue to troubleshoot, though this seems to be more of a system-wide concern and isn’t isolated to just my site. Thanks for the patience.

Hedge Against

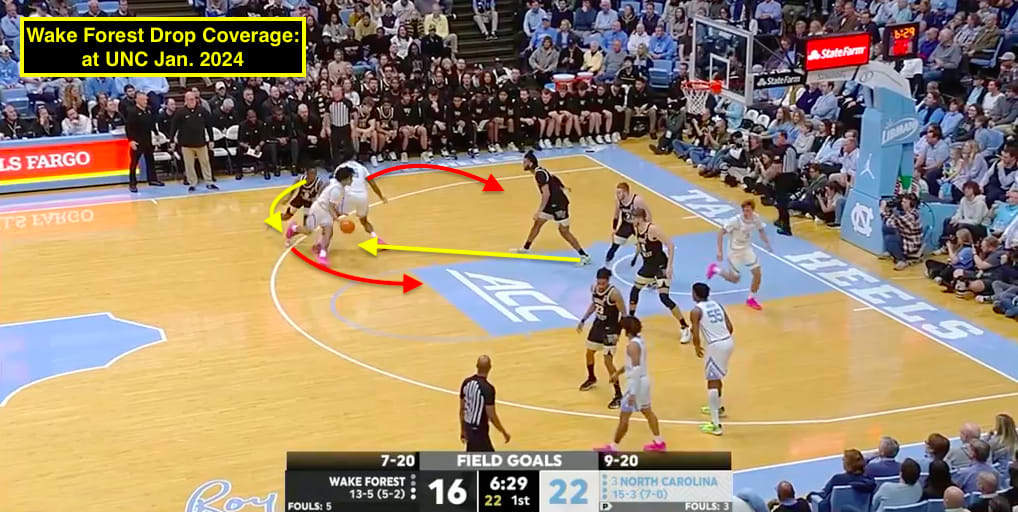

Preparing to attack Wake Forest’s pick-and-roll defense this season is different than years prior. Over the last few seasons, Wake Forest, with some exceptions, played mostly drop coverage. During the 2023-24 season, Wake Forest still hedged against certain ball handlers or used it to defend side ball screens. However, the Deacs usually had Efton Reid positioned in the drop, well below the level of the screen.

This approach is en vogue in the NBA right now, where the numbers heavily influence scheme design. It’s also what a lot of math-friendly college programs — like Creighton, High Point, Purdue and Alabama — use as a base defense.

After being deployed primarily as a drop defender last season, Reid is now in a much different capacity, which I made mention of back in November, during the second week of the 2024-25 season.

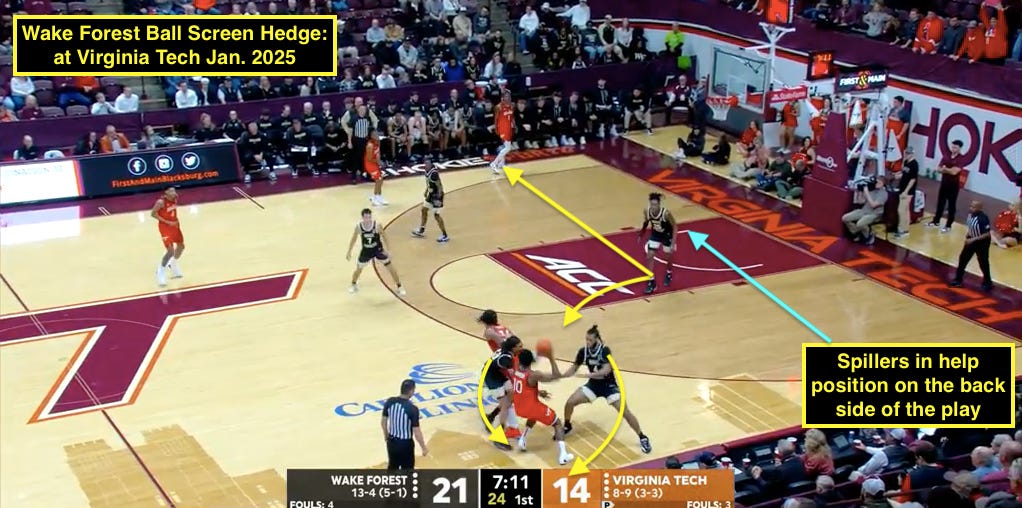

Wake Forest and Steve Forbes have shifted their base coverage to hedge ball screens. Instead of dropping deep into the paint while the on-ball defender chases over the top of the screen — working to push the ball handler into taking a tough, contested, less-efficient midrange jumper — Reid is at the level of the screen or, often, above it. In this setup, Reid tries to funnel opposing ball handlers away from the rim — sticking with them for 1-to-2 dribbles before recovering back to the screener/roll man.

For example: look how much further up the floor Reid is on this ball screen possession at Virginia Tech compared to the drop coverage possession at UNC last year.

Wake Forest isn’t an exclusively hedge defense. The Demon Deacons still mix in some looks of drop coverage, and they’ll also look to at times “weak” ball screens — downing the action and pushing ball handlers to drive with their weaker hand. That said, hedging is this team’s primary coverage.

By putting two players on the ball, Wake Forest’s defense is automatically in rotation. This is simple math: with two players on the ball — the guard defender and the big man screen defender — there are now three defenders to guard four offensive players on the back side of the play. This means that all three of those guys must communicate and be ready to fly around as help defenders. The leader of this effort is power forward Tre’Von Spillers.

On the road at Clemson: the Tigers flow into an empty-corner ball screen with their two best players: Chase Hunter (1), who is in the midst of an All-ACC season, and Ian Schieffelin (4), another potential All-ACC selection. After he screens for Hunter, Schieffelin pops out to the right corner; meanwhile, Reid is out well above the arc to hedge the screen. As Reid recovers back to Schieffelin in the corner, Spillers goes in the Jessie Bates III Free Safety Mode — floating behind the action and working to contain both Schieffelin and Viktor Lakhin (0).

Lakhin flashes to the nail and receives a pass from Hunter. The 6-foot-11 center drives right at Spillers, who meets his opposition with force and then rejects Lakhin’s attempt at the rim.

The 6-foot-7 Spillers leads Wake Forest with a 5.9 percent block rate. During ACC play, though, Spillers has blocked 6.7 percent of opponent field goal attempts when on the floor (35.6 minutes per contest), good for fourth-best in the conference.

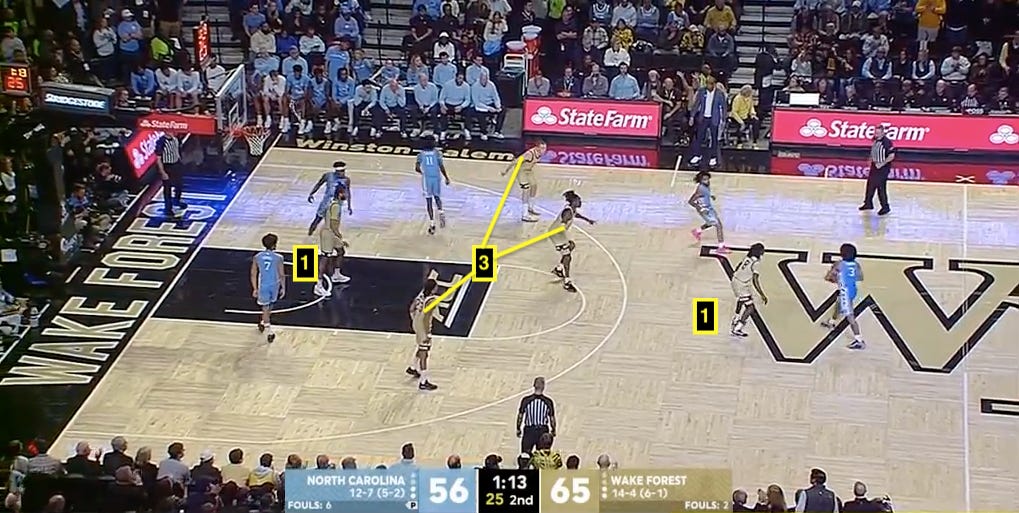

Elliot Cadeau (3) splits this ball screen as Reid hedges out. In many cases, Cadeau could use his speed to get to the rim for a layup before the defense arrives to fully contest. Spillers, however, sags off of Drake Powell (9) in the right corner and is in the paint, waiting for Cadeau.

Spillers is required to do more than just help to close down the paint while Wake Forest rotates and Reid recovers back down to his man, though that’s a priority. The southpaw must anchor things as a back-line helper, one who’s willing to fill in gaps and put out fires wherever needed.

Of course, Spillers is called upon to work as a screen defender plenty as well. Wake Forest will use Spillers to switch some screens, especially if another frontcourt player — like Juke Harris — is involved in the action. That’s a more used function of the defense when Spillers is playing the 4, next to either Reid or Churchill Abass. However, Spillers will still hedge some screens when he’s at the 4 as well.

Wake Forest has played 121 minutes (+30) with Spillers as an undersized 5 this season. According to CBB Analytics, the Demon Deacons have a defensive rating of 94.2 points allowed per 100 possessions. When Spillers plays the 5, he’s tasked with the same hedge coverages as Reid and Abass, while Harris takes over as the low-man helper, which speaks to the defensive versatility of both players.

UNC runs its “Wide” action on this play. Ven-Allen Lubin (22) sets a cross screen/pindown for Cadeau, which is immediately followed by a re-screen on the ball. Spillers doesn’t have time to hard hedge the action, but he’s at the level of the screen as Ty-Laur Johson gets over the screen. Lubin rolls downhill and that forces Harris to come off the weak-side corner and into the paint, leaving Jae’Lyn Withers (24) alone in the corner. Cadeau skips the ball to Withers. Harris takes over from here, though: he closes out short of the so-so shooter and draws the charge as Withers barrels into him while trying to get to the rim.

Up in Blacksburg, the Hokies ran some “Ram” pick-and-roll with Ben Burnham (13) setting an off-ball screen for Tobi Lawal (1), who sprints out to set the ball screen for Ben Hammond (11) — with Spillers trailing as the small-ball 5. Hammond dribbles left off the screen and Spillers throws a quick hedge at him, buying time for Johnson to recover. While Spillers is out above the arc, Harris goes to work as a team defender. Harris stunts at Lawal as he dives to the rim, and then closes out to Burnham, taking away a catch-and-shoot 3-point attempt. Burnham flows into a handoff with Hammond. Harris switches that and is in position to contest the midrange jumper.

Demon Deacon Defensive Diagnostics

The altered scheme has created some notable statistical changes from one year to the next — in terms of havoc metrics (steals, blocks, TOV), rebounding and shot chart.

Wake Forest finished the 2023-24 season Top 60 in adjusted defensive efficiency, per KenPom. As a byproduct of the drop-heavy approach, which allows the defense to guard the ball screen 2-on-2 and stay home on off-ball/spot-up shooters, opponents assisted on only 42.7 percent of their field goals (No. 20 nationally) and only 35.5 percent of their field goal attempts were of the 3-point variety (No. 108 in the country). The Demon Deacons also ranked Top 50 nationally in defensive rebound rate.

According to CBB Analytics, only 21.5 percent of opponent field goal attempts came at the rim (within 4.5 feet of the basket), which ranked in the 99th percentile nationally. This is another benefit of the drop: by sticking a 7-footer in front of the rim and staying out of rotation, it helps close of the paint and keeps the largest player on the floor in position to grab a defensive rebound.

With a different 3-point arc, the geometry of the court in college basketball is different than the NBA. Corner 3s don’t carry the same outsized value that they do for the pros, therefore teams aren’t as incentivized to target those shot zones. That said, corner 3-point attempts are often of the catch-and-shoot variety, which are inherently more efficient than an off-dribble jumper. Drop defense helps reduce the volume of spot-up 3-point attempts — thus corner 3-point attempts accounted for less than six percent of the total field goal attempts defended by Wake Forest.

Conversely, 19.7 percent of opponent field goal attempts were midrange shots that occurred outside of the paint. Opponents shot 37.2 percent on these looks. All of these numbers highlight the math-based pitch for drop coverage: it helps take away the two money shots — at the rim and catch-and-shoots 3s — while also pushing the opponent to take more off-the-dribble midrange 2s, the least efficient shot in the half court.

Like anything in life, there’s a tradeoff, though. For starters, if the defense is matched up against a strong pull-up shooter, that player destroy the drop by hitting a barrage of pull-up 3s and 2s. Certain players will light up in these moments. Plus, drop coverage can produce a more stationary, risk-adverse defense, which can impact things like turnover rate.

For three straight seasons, Wake Forest’s defense ranked outside the Top 200 nationally in turnover rate: 2022-24. After forcing a turnover on just 16.4 percent of its defensive possessions last season (No. 224), per KenPom, that’s jumped up to 20.9 percent this season, a Top 40 number in the country.

In general, Wake Forest’s havoc number are up as well. Currently, Wake Forest has a block rate of 14.1 percent, a Top 25 number nationally and one that’s on pace to be the high-water mark of the Steve Forbes era, and steal rate of 11.2 percent, which would also be the best number of a Forbes defense since his time at East Tennessee State.

Wake Forest’s guards have been opportunistic with creating styles off the hedge pressure. Moreover, the on-ball defender will get his hands vertical in the passing lane when the ball handler picks up his dribble and tries to pass over the top of the hedge.

For instance: Syracuse runs empty-side two-man action with Eddie Lampkin (44) and Chris Bell (4) on the right side of the floor. When Lampkin hands off and screens for Bell, Abass hedges out. Bell picks up his dribble and tries to pass the ball to Donnie Freeman (1) atop the key, Hunter Sallis pounces — leaping into the air, creating the deflection and grabbing the ball.

While Wake Forest may not be the 2024 Houston Cougars, nor is Sallis former Virginia point guard Reece Beekman, who was a master of this tactic, this is still an important piece of the new-look defense.

The hedge has also altered the defense’s shot chart. With the Deacs in rotation more frequently, opponents are assisting on a higher percentage of field goals — 56.4 percent — and getting up a larger percentage of 3-pointers: 44.7 percent of field goals against Wake Forest’s defense this season have come from beyond the arc — both of which are significant jumps from the 2023-24 campaign. According to CBB Analytics, 9.8 percent of opponent field goal attempts have been corner 3-point attempts.

On this possession, Florida point guard Walter Clayton Jr. (1) dribbles left off of two staggered ball screens. Alex Condon (21) sets the second screen in the left slot, and Reid hedges out at Clayton. Condon dives to the rim, which pulls Spillers off the weak-side corner to help in the paint. Clayton sees this and skips over the top for an open corner 3 from Thomas Haugh (10).

These changes continue down at the rim: 28 percent of opponent field goal attempts have come within 4.5 feet of the hoop, a noticeable jump over last year, though Wake Forest is allowing a much lower number in terms of rim field goal percentage. Despite the presence of Reid and Andrew Carr, opponents shot 65.7 percent at the rim last season against the Demon Deacons. That number — which has benefitted from the team blocking more shots — has dipped to 59.5 percent this season.

Reid has been a presence at the rim, too: 4.9 percent block rate. At times this season, he’s flashed good mobility in space — sliding with opposing ball handlers and closing things down at the hoop.

Even with the higher percentage of shots at the rim, opponents have, so far, made a lower percentage of their 2-point attempts: 45.9 percent (No. 32 nationally), down from 48.9 percent last season.

Spillers and Reid have played a combined 414 minutes together this season. Wake Forest is +95 with its starting frontcourt on the floor (+46 in 131 minutes during the recent six-game winning streak), including a defensive rating of 98.5 points per 100 possessions (88th percentile).

The key for that success has been the team’s dominance at the rim when Spillers and Reid share the floor. Opponents are shooting a paltry 53.5 percent at the rim against Wake Forest’s defense when Spillers and Reid are on the court together. On the opposite end, Wake Forest is shooting 69.8 percent at the rim when lineups that include both Spillers and Reid are on the floor.

Let those two numbers sink in: 53.5 percent and 69.8 percent. That’s a massive delta in terms of rim efficiency, and it’s the secret sauce for this Wake Forest squad.

In The Zone

Another tool in the box for Forbes and Wake Forest this season has been a 1-3-1 zone with Spillers as the middle spoke and Reid on the backline. This has been especially useful in late-game or after-timeout situations, when Wake Forest wants to throw off the rhythm or void whatever play the opposing offense just came up with during the break in play.

However, when Reid, who averages 4.8 fouls per 40 minutes, is out of the game, Forbes can get funky with how he shapes this zone concept with Spillers and Harris, two active frontcourt athletes.

Here against NC State: Harris is stationed at the free throw line as the middle spoke, while Spillers patrols the back line. Johnson is at the point of attack up top. The Wolfpack do a nice job moving the ball from side to side; however, the Deacs are unafraid of NC State’s perimeter shooters, which means they can pack the paint and short close when the ball is kicked around. Plus, by keeping Spillers at the rim, he’s able to delete any potential drives at the basket.

Marcus Hill (10) is an excellent downhill driver and he does well to get into a gap — aided by Dontrez Styles (3) setting a brush screen on Harris in the paint. Once again, Spillers is there to clean things up, though.

During this recent six-game win streak, Wake Forest — by my charting — has played at least one possession of zone defense in every game. In four of those games, Wake Forest played four or more possessions of zone defense.

Trailing in the second half at Syracuse and with Reid on the bench, Wake Forest goes zone. This time, though, the 6-foot-7 Harris, a long, rangy defender, is placed atop the zone. Spillers is still on the back line, and Parker Friedrichsen is in the middle. Syracuse has Lampkin start along the baseline, almost behind the rim. As Jaquan Carlos (5) dribbles right, Lampkin ducks in and seals on the smaller Spillers. Carlos throws a good entry pass and it looks like Lampkin has a drop-step layup, but once again, Spillers just makes a play.

Spillers finished the win at Syracuse with two blocks and three steals. On the season, Spillers now has 12 games of 2+ combined blocks and steals.

Pop Quiz: Oui or Non?

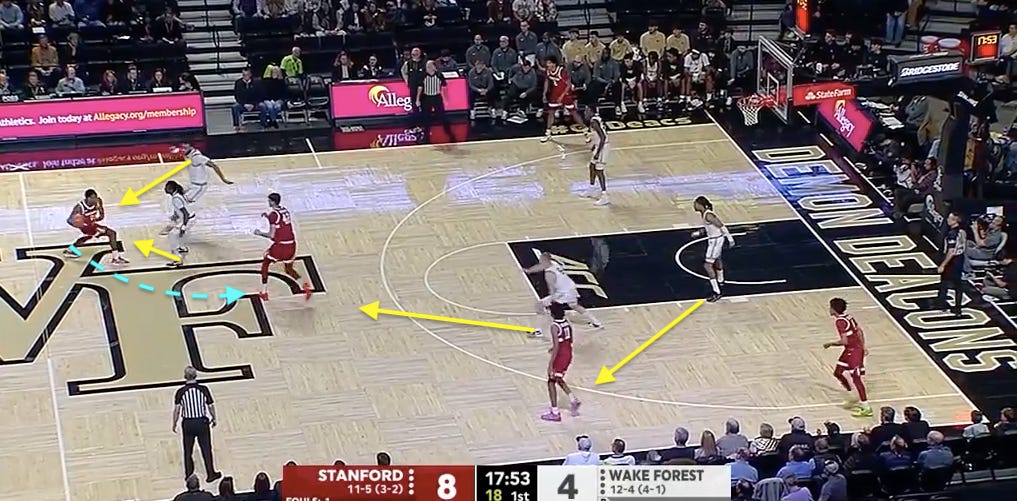

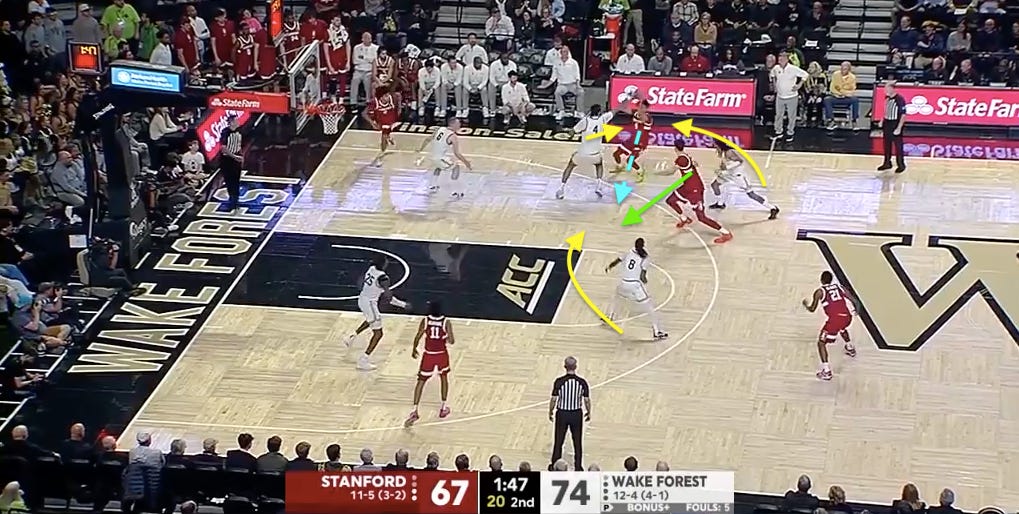

With different personnel comes different challenges for the hedge. Stanford’s Maxime Raynaud — a 7-foot-1 stretch-5 from France who can shoot (36.4 3%), dribble in space, post-up and pass (11.6% assist rate) — provides Kyle Smith’s team with a walking mismatch piece.

Whether the defense plays drop coverage or hedges ball screens, Raynaud’s ability to pick-and-pop creates a real challenge. If two defenders are on the ball handler, then Raynaud — who continues to rise as an NBA prospect — will pop or slip into open space, which is a huge problem for the defense. You can’t just let Raynaud catch the ball in space with a clean look at the rim.

When Stanford ran high ball screen action with its go-to duo of Jaylen Blakes (21) and Raynaud (42), Reid hedged the ball screens, including ones out near mid-court, and one of the three players on the back side — Cam Hildreth on this possession — would leave their assignment and either switch out to Raynaud or hard stunt in his direction.

Hildreth switches up to Raynaud, Sallis must continue this chain and switch from Oziyah Sellers (4) in the right corner to Ryan Agarwal (11) on the wing. It’s a lot of ground to cover, but Reid was tasked with sprinting from the high hedge to the weak-side corner. That full rotation is unnecessary here, though, as Hildreth (2.6% steal rate this season) digs in and creates the turnover.

Here’s another look at the same concept. Stanford runs staggered ball screens for Blakes — with Raynaud setting the second one on the right side of the floor. Reid hedges and Raynaud pops to the middle of the floor. Sallis switches off of Sellers on the left side and goes to Raynaud, again denying him a clean pick-and-pop look from beyond the arc. Reid sprints across the court to X-out and switch to Aidan Cammann (52).

Later in the first half, it’s a similar setup as Stanford tries to initiate Blakes-Raynaud pick-and-pop on the left wing. As Raynaud screens and then sets a second re-screen for Blakes, multiple Wake Forest defenders — first Spillers, then Sallis on the re-screen — buzz around underneath the action, ready to chip on Raynaud.

Ultimately, Wake Forest keeps the ball in front and forces Blakes to attempt a contested 2-pointer late in the shot clock.

As Stanford furiously tried for a late comeback at Wake Forest, the Cardinal flow into Sellers-Raynaud ball screen action. Reid hedges the ball screen, which pushes Sellers out to the middle of the Old Gold “W” near mid-court. Sellers pass to Blakes in the left slot. Blakes immediately passes back to Sellers, who runs into another step-up screen from Raynaud. Instead of popping, Raynaud dives to the rim, while Reid again hedges the screen — now on the right side of Sellers.

For a second, it looks like Raynaud will have an uncontested dive to the rim; however, Johnson has other ideas. Johnson, who averages 2.8 steals per 40 minutes this season, sprints off the left wing and — as Raynaud extends to try and corral the ball — wins the race to the spot, intercepting the pass for a huge defensive stop.

UNC at Wake

During Wake Forest’s next home game, the North Carolina Tar Heels rolled into Winston-Salem. The Heels lack a stretch-5 dimension like Stanford, and this is far from a vintage UNC squad; however, there’s still a lot of perimeter talent on this roster, including projected first round picks in this year’s NBA Draft: Drake Powell and Ian Jackson.

UNC coach Hubert Davis also had a few tactics built in to counter Wake Forest’s hedge.

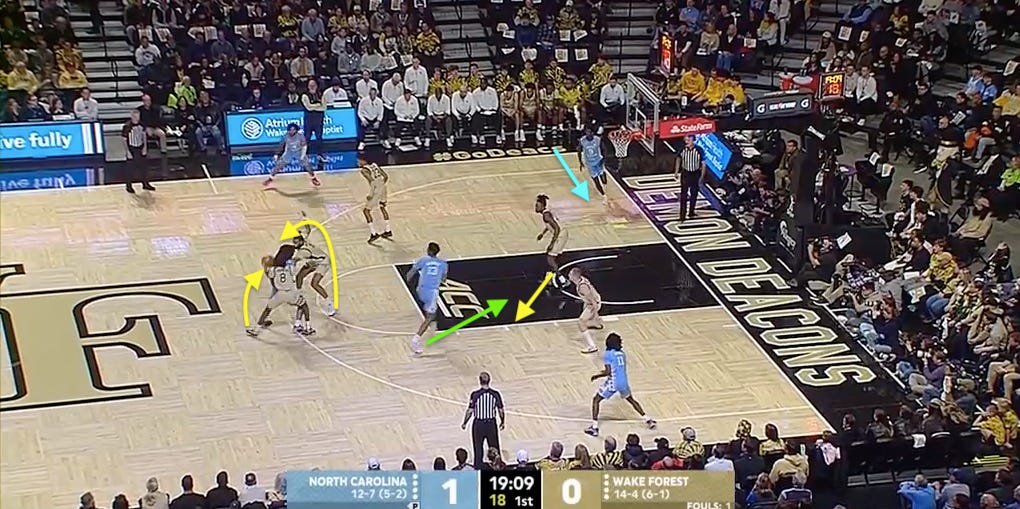

On the first possession of the game, UNC ran 5-out Zoom action for Cadeau coming out of the right corner. Atop the key, as Washington hands the ball off to Cadeau, Reid hedges the screen. Jalen Washington (13) dives into the open lane. Spillers, the designated low-man, peels off the corner and is in the there to tag Washington. Instead of remaining stationary in the left corner, Powell (9) cuts down the baseline to the mid-post area.

While this back-side movement creates a shorter closeout for Spillers when the ball is swung to Powell, it also makes for a quick catch-and-shoot opportunity, with some movement, against a rotating defense.

Powell is a good 3-point shooter (38 3P%), so keeping spaced him out beyond the arc is perfectly fine. The movement is more of a way to get Powell and his athletic finishing skills into pockets of space.

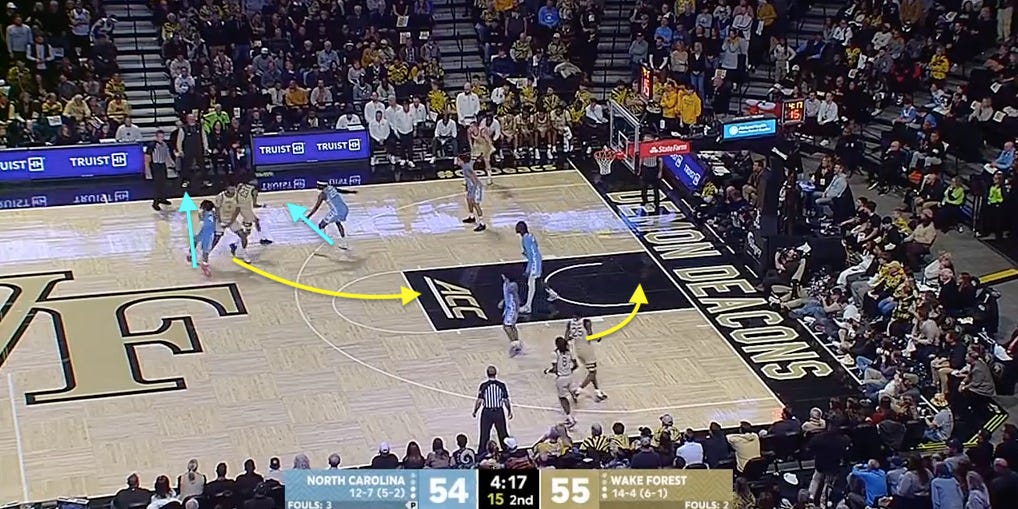

Powell tried the same thing in the second half. UNC runs its “Wedge Roll” action on the right side of the floor. RJ Davis (4) screens for Lubin, who then sets an empty-corner ball screen for Cadeau. Reid hedges out, which leaves Lubin open on the roll to the empty side. In order to help on the roller, Spillers must peel over from the left wing to the middle of the lane. Powell sees an opening and cuts to the nail, creating another midrange jumper.

While UNC found points on these Powell cuts, the offense would probably like to create more efficient looks with this tactic. Powell showing off the midrange touch is nice, but he should be looking to catch and attack — put the ball on the deck and pressure the rim, which is something UNC struggled with in this game.

UNC also tried to involve Powell’s movement in “Short Action” — a cut to or along the strong side during ball screen action — as a passer. This is a good way to attack a hedging defense.

Here, as Cadeau and Washington run high pick-and-roll from a Horns set, and Spillers hedges out at Cadeau, Powells cuts up along the right side of the floor. Powell receives an outlet pass from Cadeau against a scrambling defense. In theory, Powell could try to throw a quick pass to Washington on the dive, or look to skip it to Davis on the weak side if Sallis comes off of him to tag the roller.

Well, that’s exactly what happens, Sallis rotates down to Washington, taking away the quick pass option. Powell goes to his next progression and skips the ball wide toward Davis. Despite his struggles this season, a clean catch-and-shoot for Davis is still a great option for UNC. The pass from Powell, however, is a little high, and it forces Davis to leap for the reception. That slight readjustment is enough for Wake Forest to rotate with precision. Sallis closes out on Davis, and Washington picks up an offensive foul for an illegal screen as UNC tries to reboot the possession with a second pick-and-roll action.

Later in the second half, UNC sets up for a pick-and-roll with Davis and Washington in the right slot. Washington doesn’t set the screen; he slips out. Reid doesn’t fully hedge out at Davis, though he’s still several feet above the arc and far outside of the paint. Davis passes to Cadeau on the wing as Washington cuts hard to the rim. Reid, however, is in good position as he mostly sticks with Washington. When Cadeau tries to loft in a pass, Reid is able to deflect the ball off of Washington and create another turnover.

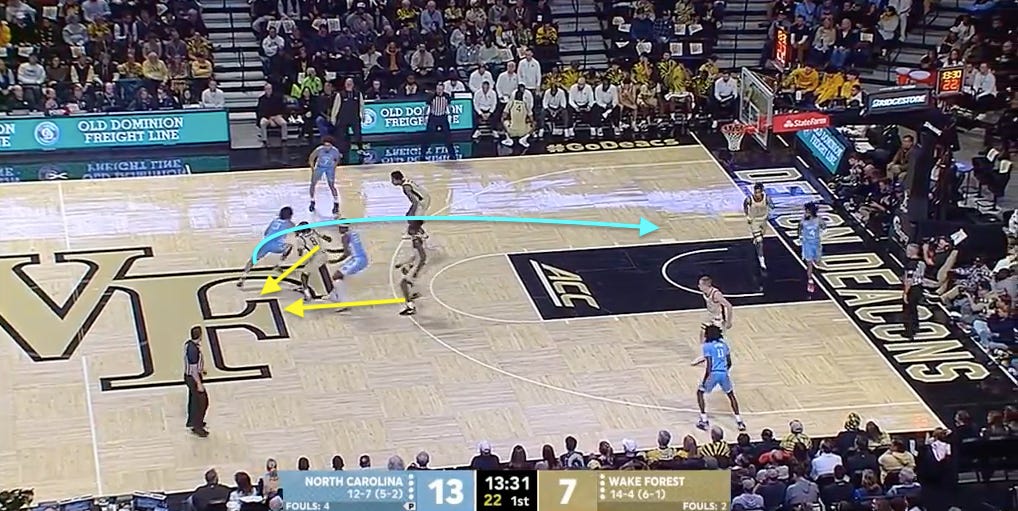

One of the things UNC had some success with against the hedge — leading directly to points on multiple occasions — was with its guards rejecting ball screens. When the defensive center gets set to hedge the action, he’s loaded up at the opposite side of the screen.

So, by quickly dribbling away from the screen, the ball handler can get by his defender and into space — without an immediate help defender in his path. UNC runs Horns Out action here into a step-up screen for Cadeau from Lubin. Cadeau starts right in the direction of the screen and then crosses left, rejecting the screen and finding oxygen as he blows by the first line of defense and gets to the rim for a layup.

Any defense that hedges should anticipate this type of stuff: ball screen rejections, Short Action, short-roll playmaking — it’s all on the table. Wake Forest knows that stuff is coming, but it’s still willing to live with that if it comes with so many other benefits. This approach — along with the ability to mix in that 1-3-1 zone — is working.

Overall, this was an impressive defensive effort from the Demon Deacons, who held the Heels to 0.91 points per possession. Going back to the 2007-08 season, this marked the third-most efficient defensive performance for Wake Forest against UNC, per the Bart Torvik database:

2/12/2020: 0.84 points per possession

1/5/2014: 0.906 points per possession

1/21/2025: 0.907 points per possession

UNC missed some good look in this game, especially Jackson (1-of-7 3PA) who couldn’t connect on a couple juicy catch-and-shoots opportunities — ones that went down for him a few weeks ago in Raleigh vs. NC State.

TLJ

While the defense has hummed this season, Wake Forest’s offense is looking to get on track, though there are some encouraging trends to point toward with the inclusion of Johnson to the starting lineup, who was inserted into the first five after the holiday break. The Demon Deacons have won all six games with Johnson as their starting point guard.

During that stretch, dating back to the Syracuse win, Wake Forest has scored 119.6 points per 100 possessions in the 175 minutes with Johnson on the floor (+65), outscoring opponents by nearly 23 points per 100 possessions. More importantly, outside of the closing minutes of the UNC game, Johnson has done a better job taking care of the ball, which seemingly kept him on the fringes of the rotation for the bulk of the season: Wake Forest’s offense has a turnover rate of only 10.8 percent with Johnson on the floor over this six-game streak.

According to CBB Analytics, Wake Forest scored a paltry 101.9 points per 100 possessions over the first 13 games of the season. Sallis shot 45.2 percent from the floor and just 27.1 percent from deep (5.4 3PA per game) in this baker’s dozen of games. While his 2-point efficiency has remained high, Sallis has shot the ball better from deep these last few weeks: 35.5 percent (5.2 3PA per game) on his 3-point attempts since Dec. 31.

While Johnson can make some head-scratching turnovers (32% TOV rate), there’s no denying his speed, creativity and unselfishness on the ball (21.2% assist rate). He wants to set guys up and create open looks for his teammates, which has sparked the offense. His presence also allows Sallis to shift to more off-ball usage, with fewer play initiation components. Sallis gets to be an attacking guard, one of the best in the country.

According to CBB Analytics, Johnson — over the last six games — has averaged 2.6 assists per 40 minutes where the shooter scores at the rim, which ranks in the 96th percentile nationally. He’s also averaged 1.3 assists per 40 minutes that have resulted in corner 3-pointers (98th percentile). Johnson also now has 5+ assists to four different teammates: Spillers (13), Hildreth (7), Sallis (6) and Reid (5).

The upshot: with Johnson’s ability to get by defenders with the ball in his hands, along with and his floor vision, he’s created looks from some of the most efficient spots on the floor.

That said, even with the positive indicators from the last three weeks, Wake Forest is still heavily reliant on midrange scoring to prop up the offense. During the six-game streak, 44.1 percent of Wake Forest’s field goal attempts have come on 2-point attempts away from the rim: between the restricted area and the 3-point arc. That’s a high volume of midrange attempts, and the Deacs have hit a sizzling 48.7 percent of these looks (74-of-152 FGA), per CBB Analytics.

An offense that dependent on success in the midrange could light up as a regression candidate — one that’s hitting an unsustainable amount of lesser efficient shots against so-so ACC competition. However, Sallis is one of the top tough shot makers in the country. With his combination of size, strength and touch, he doesn’t need much separation to get to his jumper. He just needs to be able to get to his spots.

Sallis has been on a heater from the midrange this season, too. He’s shooting 59.5 percent (92nd percentile) in the paint but outside the restricted area, where he’s averaging 4.6 field goal attempts per 40 minutes from (98th percentile). Sallis is also 3.7 2-point attempts from outside the paint per 40 minutes (95th percentile) and he’s hit 44.4 percent of those looks (74th percentile). This is ridiculous shot making from Sallis.

Snake Forest

The matchup with UNC proved to be a tough one for Sallis, who had one of his least efficient games of the season: 0-of-6 3-point attempts, 0-of-2 free throw attempts, three turnovers and no assists. As a team, Wake Forest shot just 2-of-15 (13.3 3P%) from beyond the arc and turned the ball over on 19 percent of its possessions.

This game wasn’t about a pretty offensive performance, though. It was about finding enough points to keep the ship afloat while the defense led the way. For the offense, this meant getting to the line — which Hildreth accomplished (10-of-12 FTA), in part because of Wake Forest’s willingness to post him up on UNC’s smaller guards — and hitting tough, contested midrange attempts against UNC’s drop coverage. Sallis had seven field goals in this game — all from the midrange.

UNC primarily plays no-middle, drop coverage defense. When the Tar Heels guard ball screens, the center defender usually drops below the level of the screen. When it’s possible, UNC’s guards will also look to “Weak” ball screens and push opposing ball handlers to drive with their off/weaker hand.

On this possession, Sallis runs right to left across the Iverson screens from Spillers and Harris. Hildreth passes to Sallis on the right wing and Wake Forest launches Wedge/Ram pick-and-roll — Harris screens for Spillers, who lifts to set a run-out ball screen for Sallis. Cadeau angles his body between Sallis and Spillers; he wants to funnel Sallis to the left. This is the “Weak” concept. Sallis is ready, though. He drives left and, with James Brown (2) below the level of the screen, then “snakes” back toward the middle of the lane for a short pull-up 2.

This “snake” term refers to a pick-and-roll maneuver where the ball handler drives back laterally away from his original path — and gets between the screener (Spillers) and the screener’s defender (Brown). Basically, it allows the ball handler to split the two defenders as a counter and find free real estate for a midrange jumper. Wake Forest legend Chris Paul, one of the greatest midrange shooters in the history of basketball, has pioneered this concept in the NBA.

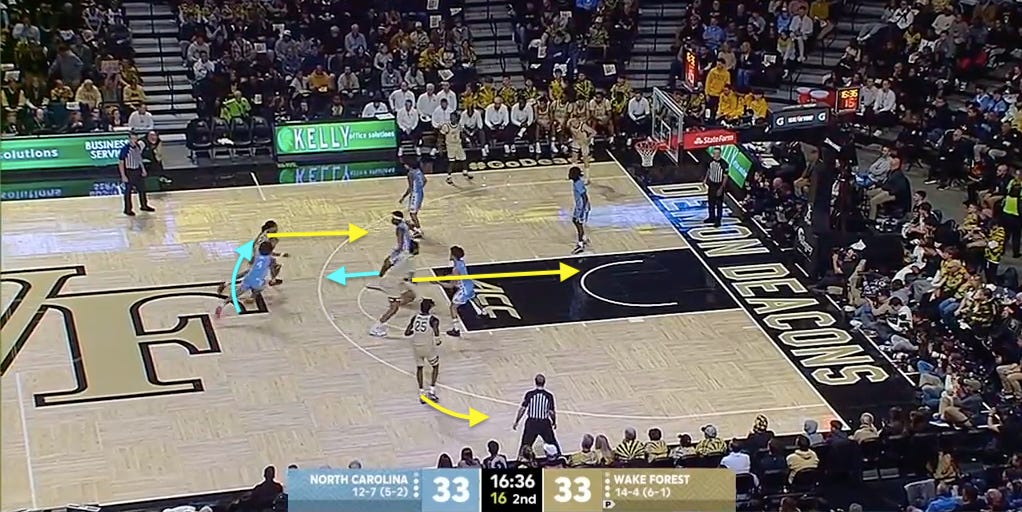

Forbes and Wake Forest also took advantage of the size disparity at the guard positions by having the 6-foot-5 Sallis put UNC’s on-ball defenders on his hip.

An important piece of drop coverage defense is having guard defenders who will fight over the screen in rearview pursuit and pressure the ball handler from behind. This can bother a lot of different players, but Sallis is so comfortable in tight spaces, looking for his jumper. He played with good patience when defended by the shorter 6-foot tall Davis.

Wake Forest runs Sallis off more Iverson screens and then flows him into 5-out Zoom action: Reid has the ball in the middle, Spillers sets a down screen and Sallis runs off the down screen and into the handoff with Reid. UNC is in drop coverage; Lubin is at the free throw line when Sallis turns the corner above the arc.

Once he starts to drive downhill, Sallis slows down; he hits the deceleration button and Davis lands on his right hip, which is here Sallis intends to keep him. Sallis gets to his spot and lifts up for another jumper inside the paint.

With Lubin several feet off of him and Davis lacking the length to truly bother his shot, Sallis is the one leading the dance here. He hits his marks to perfection.

Finally, Wake Forest also involved Reid on the the short roll. When UNC weaks ball screens, it will sometimes have the 5 come up closer to the level of the screen as added containment for the ball handler. This, essentially, puts two defenders on the ball and leaves the middle of the floor open for the short roll. On the defensive possession, Davis and Lubin (near the level of the screen) apply aggressive weak coverage on Sallis, which opens up the short roll for Reid.

Here’s this play in action as Wake Forest runs “Horns Twist”, one of its go-to pick-and-roll play designs: the ball handler will drag out the initial ball screen toward the sideline, and then pivot and use a second ball screen back toward the middle of the floor. With Davis and Lubin committed to the ball, Sallis hits Reid on the short roll. UNC’s weak-side defense collapses, leaving Johnson open on the wing and, more importantly, Spillers cutting to the basket.

This is beautiful tic-tac-toe connectivity from Wake Forest, but it was one of only a few highlight passing sequences. Wake Forest had just seven assists against UNC on its 22 field goals.

This recent run of Wake Forest will be put to the test over the next two weeks. Duke brings the No. 2 defense and No. 4 offense in the country to the LJVM Coliseum this weekend. That’s followed by a trip to Louisville, where former Wake Forest assistant coach Pat Kelsey has turned the Cardinals into a high-flying, 3-point-launching machine on offense. Pitt is in the midst of a backslide, but the Panthers still offer a sophisticated pick-and-roll attack, led by Jaland Lowe, who carved Wake Forest up in the ACC Tournament last year, and a rugged Top 65 defense. After the Pitt game, Wake Forest will fly cross-country to Stanford, where they’ll again have to deal with Blakes and Raynaud.

It’s go time.