Power Play: How Duke created numerical advantages against Illinois

Duke generated 2-on-1 situations with down screen actions in early offense, flare screens and handoffs to exploit the drop coverage, and spacing the floor around designed post-ups

New York City may be the greatest city in the world, but not everyone is guaranteed to have a good time on their first big trip to the Big Apple. Just ask the Illinois men’s basketball team, which was defeated by Duke 110-67 at Madison Square Garden last Saturday.

In the blowout victory, the Blue Devils scored 1.50 points per possession, posting their second-best single-game offensive efficiency of the season — only trailing their 1.60 mark against Stanford the previous Saturday. According to Bart Torvik’s database, which goes back to the 2007-08 season, this was the second-most efficient offensive performance from Duke against a Top 30 team in terms of adjusted efficiency margin. The last time Duke eclipsed the 1.50 points per possession benchmark against a Top 30 team occurred back in Dec. 2015, when Brandon Ingram and Grayson Allen combined for 40 points during a win over Indiana.

Matched up against one of the nation’s top interior defenses, the Blue Devils scored 52 points in the paint and drilled 12 3-pointers, while assisting on 70 percent of their field goals. This was a clinic. Here are a few ways Duke found success against Illinois: using down screen actions in early offense, flare screens and handoffs to exploit the drop coverage and spacing the floor around designed post-ups.

Widen the scope

Led by the grab-and-go playmaking and open-floor passing of Cooper Flagg and Sion James, Duke played with great pace in this game, shooting 10-of-13 on field goal attempts with between 20-30 seconds on the shot clock.

Duke’s transition attack was, of course, fueled by a defense that allowed just 0.91 points per possession. However, this wasn’t a nonstop fast-break affair; Duke forced only nine turnovers (five steals) and scored 12 fast-break points. Instead, the Blue Devils were excellent in various forms of early/secondary offense, including this “Drag” ball screen with Flagg and Khaman Maluach. Tyrese Proctor builds off of the initial advantage from Flagg, attacking a closeout from Kasparas Jakucionis (32). The driving attempt go doesn’t for Proctor, but with Tomislav Ivisic (13) forced to contest, the rim is open for a Maluach put-back bucket.

The Blue Devils attempted 72 field goals in this game — with 34 of those shots coming at the rim: 47.2 percent of the team’s total field goal attempts. That’s well above the season average for Brad Underwood’s club. Entering this game, less than 28 percent of the field goal attempts against Illinois’ defense had come at the rim, per CBB Analytics. Not for nothing, Duke shot 64.7 percent (22-of-34 2PA) on these looks, too.

Another way that Duke was able to create quick advantages in these situations was with its “Wide” action, which opened up the floor and put pressure on Illinois’ deep drop coverage.

Wide action — or “Single Away” — is a 5-out high pindown screen set by the player at the top of the key for a guard/wing on the weak-side wing. The angle of the screen is designed to allow the guard to cut across the formation and toward the ball. For example: as James initiates the action, Maluach sets the Wide screen on Dra Gibbs-Lawhorn (2) for Kon Knueppel — with Ivisic dropped deep into the paint, well below the level of the screen.

As Knueppel exits Maluach’s screen, he can look to let it fly and shoot a 3-pointer, or he has the option to curl hard and drive downhill. With the floor spread — all three players outside of the action are excellent spot-up shooters — Illinois is forced to defend this action 2-on-2: on-ball defender and screen defender vs. Knueppel and Maluach. However, with a tight curl from Knueppel, he’s able to separate from Gibbs-Lawhorn and turn this into a de facto 2-on-1 scenario against Ivisic — with Maluach (54 dunks, 84.2 FG% at the rim) diving to the basket.

Knueppel is a patient playmaker, and he’s comfortable creating in live-ball situations in the final third of the floor. His ability to make quick, decisive choices late in a drive is key when facing drop coverage. While Knueppel could drive all the way to the rim, he has the savvy to get Ivisic to bite and take a step toward him. Once that happens, you may as well add two points to the scoreboard — here comes the lob for Maluach.

In the second half, the same setup unfolds with Proctor and Patrick Ngongba. Isaiah Evans and Knueppel space out to the corners, clearing the middle of the floor. Flagg initiates and calls for the action.

As Proctor curls hard to his right, moving in the direction of the ball, Ngongba clips Will Riley (7) with a screen, creating some separation for the Aussie. Flagg hits Proctor in stride and it’s another 2-on-1 for Duke. This time, Proctor decides to keep it and score over the 7-foot-2 Ivisic at the rim.

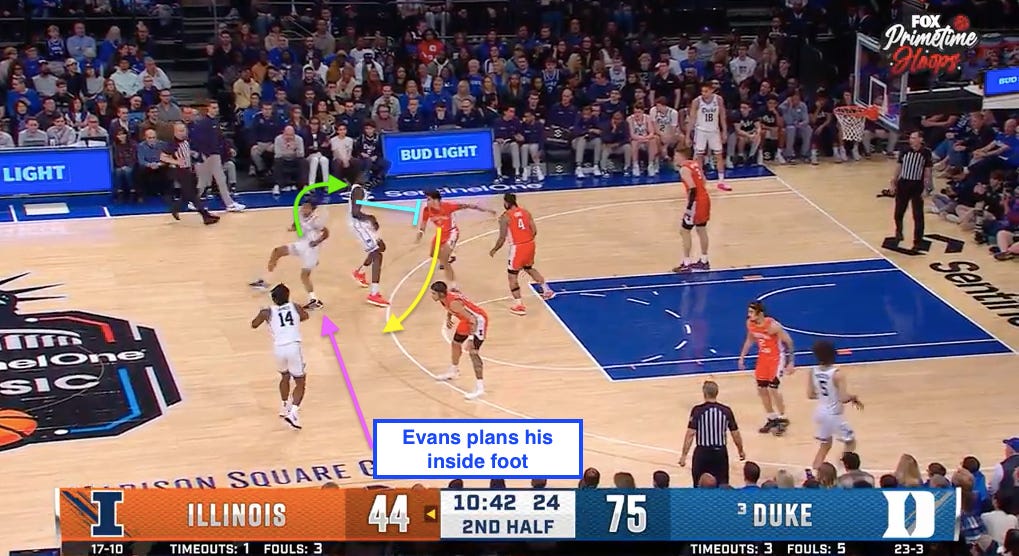

A few minutes later, with the game spiraling out of hand, Duke snaps into Wide action once more. Evans is the target on this possession. Riley, who was burned by Proctor earlier when he fought over the top of the screen, elects to go under the screen and try to meet him on the other side, thus preventing the downhill curl.

Evans is quickly establishing himself as a smart off-ball mover. He reads Riley’s coverage, plants his left foot and fades away from James, drifting back to the left wing. This forces Riley to adjust his flight pattern, giving Maluach enough time to set a re-screen for Evans, ultimately creating an open look for a catch-and-shoot 3-pointer.

Now, once the defense has seen different versions of the Wide action, Duke can get into some of its secondary progressions.

On this play, Mason Gillis will reject the Wide screen from Maluach. Instead of playing off of the curl, Duke reorients around Maluach at the elbow. James passes to Maluach and moves toward him. Maluach fakes a handoff to James, who cuts around the center, gaining separation from Kylan Boswell (4). As the play progresses, Maluach delivers the ball to James on the cut, setting up another quick 2-on-1 opportunity against Ivisic's drop coverage.

James continues to be an important source of paint pressure for Duke. According to CBB Analytics, James is shooting 66.7 percent at the rim this season — with over 44 percent of his field goal attempts (91st percentile) coming within 4.5 feet of the basket.

Earlier this season, during their road game against SMU — another team that primarily employs drop coverage — the Blue Devils utilized a similar strategy with Wide action.

Here, Flagg initiates this possession from the left side of the floor. Malauch sets the Wide screen for James in the right slot. James attacks the drop coverage of Samet Yigitoglu (24), collapses the defense and sprays out to an open corner 3-ball from Proctor.

During the second half at SMU, it’s Flagg’s turn to attack off of the screen. He receives this pass from Proctor near the right slot, drives middle, caves in SMU’s help defense and kicks back to a relocating Proctor for another 3-pointer.

Extra Flare

Currently, there are 11 players in the ACC who are shooting 36.5 percent or better from beyond the arc while averaging 10+ 3-point attempts per 100 possessions. Duke accounts for three of the player on that list: Evans (18.2 3PA per 100, 45.8 3P%), Proctor (11.7 3PA per 100, 40.9 3P%) and Knueppel (11.8 3PA per 100, 38.3 3P%). The Blue Devils are the only team to have more than one player hitting these benchmarks this season.

(Among high-major freshmen: Evans and Knueppel are two of only seven players with 10+ 3PA per 100 possessions and 36.5 3P% — along with Tre Johnson of Texas, Auburn’s Tahaad Pettiford and Christian Anderson of Texas Tech.)

These are three players who are high-volume, quick-triggers shooters with NBA range. That kind of combined 3-point shooting talent on one roster opens up a lot of flexibility in the half court, especially when one of more of those players can also attack downhill as a driver.

During the Illinois matchup — as the trio of Knueppel, Proctor and Evans combined for 44 points (on 26 FGA), eight assists and only one turnover — Duke leveraged their off-ball skills to attack the pocket of space left open by Illinois’ drop defense. When the defensive center refuses to leave the paint, even when his man is lifted out to the arc, the offense can counter with off-ball screens and handoff actions.

A key indicator for these types of plays is when Duke positions Maluach, Ngongba or Brown in the corners. They aren’t out there to catch-and-shoot or draw a defender out of the paint. Duke wants to use them as screeners.

I call this set play “Stack 5 Down Chest,” a strategy Duke has executed effectively in recent weeks against several ACC teams, including UNC and Stanford, both of which use variations of drop coverage. The action starts with Flagg and Knueppel stacked in the middle of the floor and Maluach in the right corner. Notice: with Maluach spaced beyond the arc, Ivisic still starts with two feet in the paint.

Next, Knueppel will pop to the right off a brush screen from Flagg. James will pass the ball to Knueppel on the wing and then cut down after using a back screen from Maluach — following a fake handoff from Knueppel to Duke's point guard. As James continues his cut to the weak-side corner, Knueppel will make a quick pass back to Flagg, positioning Duke with all the right pieces in place.

With the right corner empty and Ivisic dropped into the paint, Maluach lifts up and sets a rip/flare screen on Boswell for Knueppel, who cuts toward the vacant corner. Flagg passes over the top.

When Knueppel catches the ball in space, Maluach dives to the rim. As Boswell fights to get over the screen — thus putting him slightly behind the action — Duke has created another 2-on-1 against Ivisic’s drop. Knueppel challenges Ivisic at the rim and misses, but the contested shot leaves the basket exposed and Maluach soars in for a put-back 2.

Here’s Duke running this same action for Knueppel against UNC’s drop. This time, though, the defense converges on Knueppel with RJ Davis (4) fighting over and Ven-Allen Lubin (22) racing out on the freshman shooter. Meanwhile, as Maluach rolls, UNC’s help-side defense caves in: Seth Trimble (7) leaves Gillis to tag Maluach in the lane and prevent a lob. That, however, opens up the skip pass for Knueppel.

A few possessions later in the Illinois game, it’s the exact same setup, though the pieces are rearranged. Gillis is in for Flagg. Ngongba is in for Maluach. Evans is now the target who will take advantage of Ngonba’s flare screen. The success of this play hinges on Ngongba’s ability to make contact on the screen without fouling Riley. Ngongba hits his mark, Evans breaks free and Gillis drills him for a catch-and-shoot triple.

From earlier in the week, here’s the same set at Virginia, which produces another corner 3-pointer for Evans, assisted by Gillis. Although on this possession, the passing window for Gillis is slightly tighter as Virginia’s center, Blake Buchanan (0), leaves the paint and follows Ngongba out toward the arc. Regardless, the Blue Devils make it work, thanks in part to another solid screen from Ngongba.

Razor Slim Edge: Isaiah Evans + Patrick Ngongba

Often, Duke will use the off-ball gravity of Knueppel, Proctor or Evans to open things up for another player in the half-court setting. When those guys are involved in the action — either as the person setting or using the screen — it causes a defensive reaction. The defense doesn’t want one of those three cutting into space for an open 3-point look. This level of concern pulls defenders in other directions and creates indecision. Those interactions are exploitable for Duke’s offense.

Moreover, it’s a great way to amplify frontcourt passers like Maliq Brown and Flagg, or create gaps for cut finishers like James and Maluach to dart into. At times, they can also be used in conjunction with one another. It’s a powerful half-court action to blend Knueppel, Evans and Proctor in off-ball sets.

At Clemson, for example: Duke runs its “L” series, which starts with Knueppel coming out of the right corner and zipping up and off of down screens from Flagg and Brown, flowing into a high-post touch for Brown. As Knueppel clears to the weak side of the floor, Proctor lifts from the corner to set a flare screen on Knueppel’s defender, Jaeden Zackery (11).

Knueppel cuts toward the corner off the flare, forcing Chase Hunter (1), who’s guarding Proctor, to briefly adjust his body position. Hunter turns his shoulders, preparing to help Zackery on Knueppel. In that split second, however, Proctor takes advantage of the opening, cutting into the unguarded interior space as Hunter briefly loses track of him. Meanwhile, Flagg (44.4 3P% in ACC play) and James (48 3P% in ACC play) space to the right and pull the weak-side defenders out of the lane.

This has been a money play for Duke all season long, but the weak-side flare action is only one piece of the series. Instead of having the player set the flare screen and slip to the basket, Duke also lets that player (Evans) set the flare screen and then transition into a handoff with the 5 (Ngongba). Alternatively, the player might fake the flare screen, slip out and then sprint into the handoff, which is exactly what Evans does in this first-half possession against Illinois.

Similar to Hunter in the Clemson game, the possibility of the flare screen from Evans causes Riley, his defender, to hesitate for a half-second — unsure if he’ll need to switch or provide some help to Boswell. That’s the threat of Knueppel. However, Duke will leverage that and have Evans slip the flare screen and then tight curl around the handoff from Ngongba. Shooter’s touch.

This is a lot to ask one player to navigate as an off-ball chase defender. Plus, the handoff is a great way to attack the deep drop. Riley never fully recovers into the play, and Ivisic is dropped deep in the lane — several steps under the free throw line — when Evans curls above the arc. There’s no help defender for Riley and that leads to a lightly-contested jumper from one of the best 3-point bombers in the country.

With Brown sidelined due to injury, Jon Scheyer turned to Ngongba as a frontcourt playmaking hub against Illinois, which is a sign of things to come for the freshman center. Duke is now +89 in 151 minutes with Ngongba as the lone 5 on the floor (Maluach and Brown on the bench) this season, including an offensive rating of 133.8 points per 100 possessions.

Evans has been on the floor for 85 of those 151 minutes — during which Duke has an offensive rating of 139.5 points per 100 possessions.

It’s not hard to see the chemistry and archetypal fit between the two: a frontcourt passing hub and an elite off-ball mover. The freshman center has 11 assists on the season — six of which have gone to Evans, per CBB Analytics.

Ngongba (6-11, 250) is so talented for a young big. He has excellent hands and touch inside of 15 feet, which he blends with skillful footwork and a feel for making plays in space. He’s also a low-post bully, who can take advantage of his strength 1-on-1 in the post (23-of-33 2PA, 69.7 2P% this season).

Later in the first half, Duke runs the same action: “L” series for Proctor into a high-post entry for Ngongba. Evans lifts from the corner and it looks as though he’ll set the flare screen for Proctor. Once again, Evans slips the flare screen and dashes straight into the handoff from Ngongba. Instead of looking for his 3-ball, Evans curls hard and gets downhill — now with Carey Booth (6-10, 215) at the rim instead of Ivisic (7-1, 255).

This is the next step for Evans, who slashes to the rim and draws a foul: getting stronger and developing catch-and-go counters when defenders run him off the line. As Evans has fulfilled the role of bench gunner for Duke this season, starting with his out-of-body experience against Auburn, nearly 83 percent of his field goal attempts are of the 3-point variety. He’s attempted only 20 2-point field goals (50 2P%) and 21 free throws (81 FT%). Those numbers are largely influenced by limited playing time in a crowded backcourt, but Evans still relies heavily on his perimeter jumper to generate offense.

That said, he possesses one of the most dangerous skills one can have on the basketball court: 3-point shooting. You can see opposing teams react to his presence on the floor. Evans has the ability to distort defenses with his gravity and the length to finish over contests thanks to a high release point — all while showcasing a creative range of unorthodox shot-making skills. Once he adds muscle and becomes better able to play through contact, it’ll unlock his driving game, making him an even tougher matchup on the perimeter.

Early in the second half, it’s the same setup: “L” series for Knueppel into a high-post feed for Ngongba. This time, though, Evans actually sets the screen. In fact, he sets a great screen — knocking Jake Davis (15) to the ground. This is how you know Evans is wired to score: when involved in movement sets, he understands the importance of setting good screens, which will create openings for both his teammates and himself. All three of Evans, Proctor and Knueppel do an excellent job working as screeners.

(Quick note: Some basketball folks refer to this concept — a rip/flare screen into a handoff — as “Peja” action, given how frequently Rick Adelman ran it for current ACC basketball dad Peja Stojakovic when the two worked together with the Sacramento Kings. However, I usually refer to this as “Razor” action.)

Ngongba could throw it to Knueppel, who is alone in space, but he opts to run another handoff with the man they call Slim. Evans’ footwork curling these handoff actions is terrific, and Ngongba makes sure to create some contact with his screen, thus generating more separation between Evans and the chase defender, Tre White (22). Evans grabs the ball and rockets downhill; the suddenness and determination of his drive almost seems to catch Ivisic by surprise. The big fella ends up on his heels, trying to backpedal, as Evans slashes to the cup.

In this one play, Evans showcases his confidence, length and touch while extending for this off-hand finish over a 7-footer planted in the paint.

Finally, the roles are reversed on this possession: Evans is the player zipping up the down screens from Flagg and Ngongba, while Knueppel starts in the weak-side corner and lifts to set the flare for Evans. As Knueppel runs toward Ngongba, Flagg mirrors the flare action on the left side of the floor, screening for James and slipping into space.

Boswell (6-2, 205) is able to recover back to Flagg (6-9, 205), but the future No. 1 pick has far too much of a height advantage once he catches the ball at the nail. It’s a quick turn-and-burn from Flagg, who sinks the fadeaway jumper.

5-Out into Post-up

On the very first half-court possession of the game, Duke established one of its offensive themes for the night: a 5-out set into a post-up action for Flagg or Knueppel.

Initially, as Flagg controls the show up top, it looks like the Blue Devils are set to start with staggered down screens (“Strong” action) for Knueppel coming out of the left corner. However, instead of using the screens from James and Maluach, Knueppel rejects the pindowns and cuts to the paint.

Next, Flagg will pass the ball to Maluach in the left slot. Maluach will turn and pass the ball to James on the left wing — an ideal spot to throw a potential post-entry pass. After Flagg passes to Maluach, he’ll sprint in the direction of Proctor, who lifts out of the right corner. It appears that Flagg will set a down screen for Proctor, but instead, he slips out and sprints to the strong-side low block, using a slice screen from Knueppel. Meanwhile, Proctor keeps running and comes off a down screen from Maluach — moving in the direction of James.

With a series of moving parts, Duke creates this symmetrical look: Flagg slicing to the left block while Proctor curls to the left wing. Both of these actions orbit around Ivisic, who predictably drops deep into the paint, under Maluach’s screen for Proctor. James has options here, but he elects to dump the ball down into Flagg — never a bad choice.

Starting with good position, Flagg is able to catch and get into the paint. Illinois opts to send help for White with Ben Humrichous (3) doubling down from the strong-side wing. This is a risky play against a floor-mapper like Flagg — with James (40.8 3P% this season) one pass away. It’s an easy kick-out for Flagg, hitting an open James who lifts from deep while Humrichous closes out short on him.

Scheyer calls for a similar setup later in the first half, although some of the roles are flipped around. Gillis is in for James. Proctor starts in the left corner and cuts down to the paint, while Knueppel launches up from the right corner. After Flagg passes to Maluach, he acts as if he plans to set a down screen for the player coming out of the right corner: Knueppel. Flagg, however, slips the screen and cuts down toward the paint. It looks like he’ll once again come off a slice screen from the low guard (Proctor) down to the left block.

Maluach doesn’t swing the ball to Gillis, though, nor does Flagg cut through the lane. Instead, he rejects Proctor’s slice screen, spins and seals just outside of the lane on the right side. As Flagg goes to work for position in the post against the shorter-but-stockier Boswell, it causes Ivisic to sag off Maluach in the direction of Flagg. Now, Duke has it set up: Maluach runs the next progression, setting a down screen in the middle of the floor for Proctor.

Once again, Riley is tasked with chasing a dangerous offensive player around a screen with no immediate help from Ivisic, the screen defender. Proctor receives the pass from Knueppel with some advantage, but as Riley scrambles to closeout, the Aussie puts the ball on the deck and gets downhill. As Proctor drives, Ivisic tries to rotate back in help, but Maluach seals him deep in the paint. Proctor snakes back against the drop coverage and gets to the rim for a layup.

There were other possessions, though, when Duke decided to skip some of the window dressing and just punch the ball into a mismatch: Knueppel vs. Jakucionis.

This play starts with an early handoff exchange between James and Flagg, who passes the ball to Gillis on the left wing and cuts down toward the baseline. Gillis kicks the ball to Maluach in the middle of the floor. Maluach swings it to James, who again is in the right place to throw an entry pass. While Maluach passes to James, Knueppel leaves the right corner and ducks in against Jakucionis in the low post — sealing with deep position.

As Knueppel quickly goes to work, drop-stepping around Jakucionis for a layup, Flagg and Maluach exchange. Flagg shifts to the top of the arc, bringing Boswell — a potential help defender against Knueppel — with him and away from the rim. Regardless of Maluach’s location, Ivisic will be dropped into the paint, so instead of having two potential help defenders in the lane, there’s only one. Plus, with Maluach near the restricted area, Knueppel has a drop-off pass option if Ivisic comes at him with a hard double team.

Duke ran something similar during this after-timeout play against Stanford. Once more, it starts with a James-Flagg flip handoff in early offense. From there, Flagg passes to Gillis and cuts in the direction of the baseline. Gillis swings the ball to Maluach. James (6-6, 225) has the smaller Benny Gealer (6-1, 180) on him, so he’s the one that ventures down into the post, while Knueppel lifts from the corner to the left wing.

Chisom Okpara (10) and Gealer do a nice job switching this exchange on the fly. The larger Okpara (6-8, 240) switches to James while Gealer goes to Knueppel. James tries to post and isolate against Okpara, but the veteran forward contains his drive, which results in kick to Knueppel with the smaller Gealer on him. Duke still found the target, and Knueppel scores a bully-ball bucket in the paint.

Duke can run beautiful transition offense with all of its athletes or well-choreographed half-court sets that create synergy, build advantages and target the most efficient areas on the floor. Of course, Duke reserves the right to play matchup ball, too. With Flagg, Knueppel and James, especially, plus Proctor, Duke has guys who can punish different defenders, depending on matchups and game-time situation.

Caleb Foster, who showed signs of life late in the game against Illinois, can factor into this equation as well, though his role feels a bit tenuous at this time. Currently, there are five players on Duke’s roster averaging 1.8 or more unassisted 2-point field goals per 40 minutes, according to CBB Analytics: Flagg (4.5), Foster (3.0), Knueppel (2.3), James (2.0) and Proctor (1.8). In fact, Foster has the highest percentage of unassisted 2-point field goals on Duke’s roster: 88.2 percent. If Foster can shift to being a spark-plug driver off the bench, it adds in another dimension to this roster.

There are only two weeks left in the regular season; it’s the homestretch. March is nearly upon us. As the days (thankfully and mercifully) grow longer, the season starts to dwindle. So it goes. Let’s see how Duke takes advantage of the precious time that’s left.